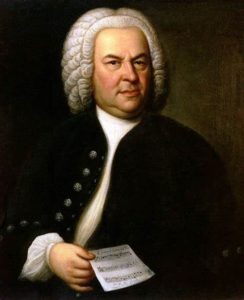

Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco, February 8 — The recital by Yefim Bronfman could not have been better. The program itself was a work of art. Robert Schumann, Arabesque in C major, Opus 18 (1839); Johannes Brahms, Piano Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Opus 5 (1853); Claude Debussy, Images, Book Two (1907); Ludwig Van Beethoven, Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Opus 57, Appassionata (1853). Strange, Brahms’ work and Beethoven’s were written in the same year.

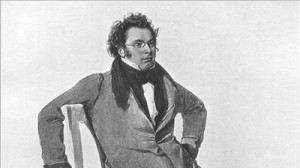

The selections are each different from each other and yet each adds to the philosophy and beauty of the whole. Opening with Schumann’s Arabesque brought something delicate and strong at the same time. It is simply beautiful, but beauty is not simple. One might draw a picture of a tree with one line for the trunk and circles for the leaves, but that is not all there is. Before the thoughtful music ends, there is an inward pull of the ropes and then we have a dream.

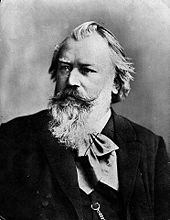

The Piano Sonata No. 3 by Brahms is a work that could have been a symphony. It has deep developments playing into the five movements which Brahms took to move from an Allegro maestoso, onward to an Andante expressivo, Scherzo: Allegro energico –these descriptive names shape so much of human stories all of which powerfully move in experience and emotion. Bronfman mastered the strength that Brahms designed into all of the music from Allegros to Andantes. It was unbelievably difficult technically, a big sound and precise playing; it is like the concentration of a quarterback running zig zag to miss being brought down. The runner and the brain and the pointed feet going where he knows to go. Watching Bronfman is a gift to see what he is doing and and hear the music that reaches our hearts.

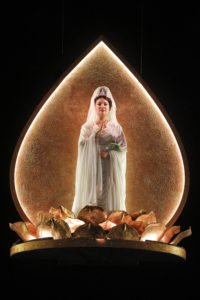

Claude Debussy has created many new sounds in his Images. We hear the Clair de lune and the L’Apres-midi d’un faune/Afternoon of the Faun, but the three Images Bronfman presented are seldom presented. Debussy was attracted to the sounds of the gamelan. In the program book, Scott Foglesong quotes Debussy on Javanese music: “Their academy is the eternal rhythm of the sea, the wind in the leaves, thousands of tiny sounds which they listen to attentively without ever consulting arbitrary treatises.” The three pieces are Cloches a travers les feuilles (Bells heard through the leaves); Et la lune descend sur la temple qui fut (And the moon sets over the temple that was); Poissons d’or. Each of the Images takes the listener to Debussy’s magical genius, and the genius of it is that the music and the images are not magic, they are real.

Now, it is Beethoven. The Appassionata overwhelms every breath the listener makes. The long first movement, Allegro assai, is almost ready for the explosive. Bronfman’s strength is focused on every theme. Beethoven finds so many ways to approach that movement: quietly, twisting it upside down, roaring, a fire-truck is coming but too late, stand there and see the flames. Oh, the fire is also beautiful. The pianist has to be able to get ahead of all this, and Yefim Bronfman completely knows what to do. The Andante, at first, seems to step away from the fire to some place for a restful time out. No way. Instead it lets the Allegro ma non troppo go Presto. Bronfman is riding the waves or maybe dancing over a volcano. He plays faster and outplays the challenges from Beethoven. It has become an array of nature’s ways to move and blow up. The audience was stunned, thrilled, checking into fabulous stars. Bronfman was able to perform everything that Beethoven offered him. It was sensational.

The audience could not let him go. The two encores were October, from Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons; Liszt’s, “Paganini” Etude No.2. Yefim Bronfman is brilliant. Find him and listen.

Emanuel Ax, pianist

Emanuel Ax, pianist Emanuel Ax and

Emanuel Ax and  Jaap van Zweden, conductor

Jaap van Zweden, conductor

Ludwig van B

Ludwig van B

Cast

Cast

This is the Dragon Palace of the Eastern Sea; making a scene under water is a fabulous event.

This is the Dragon Palace of the Eastern Sea; making a scene under water is a fabulous event. The

The

Itzhak Perlman

Itzhak Perlman