Daniil Trifonov lit up Davies Symphony Hall, Nov. 19, San Francisco. The audience was fascinated by his playing and only a few minutes into Rameau’s Suite in A minor, RCT 5 (1729/30), we were all transfixed. The program itself was a jewel: Rameau, Mozart’s Piano Sonata No.12 in F major, K.332 (300k) (ca. 1783), Mendelssohn’s Variations Serieuses, Opus 54 (1841), Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 29 in-B flat major, Opus 106, Hammerklavier (1818).

The selections were not random choices from famous composers. Each piece had special challenges for the pianist and brought unique charm and glory for the listeners.

The program was not only about the majestic music. All of these great composers were also great musicians, especially as pianists. Daniil Trifonov was playing the music which was made by and played by the best. He meets their music and brings his understanding to its complex beauties. He also plays on their level. He is there with the top seeded players. They know their game. Each one in his own way recreated playing. The program is an encounter of great pianists through nearly four centuries.

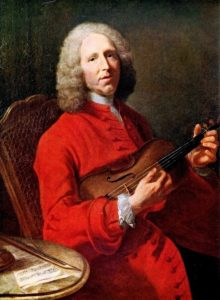

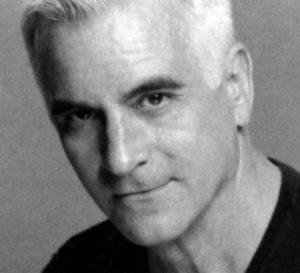

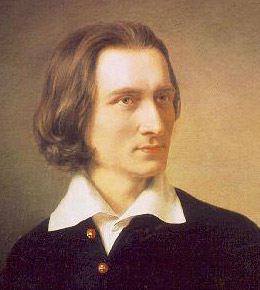

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer (1683-1764)

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer (1683-1764)

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Suite in A minor, RCT 5 (1729/30) has seven parts: Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, Les Trois Mains, Fanfarinette, La Triomphante, Gavotte et ses Doubles. The first three are named for the dances popular for 17th century composers, like JS Bach. They create a serious environment. This is for harpsichord virtuosi ready to play the multiple sounds of their tradition. However, with Trifonov at the keyboard, these have an enchanting delicacy. The next four parts are “character” music rather than from the dance forms. Les Trois Mains calls upon the pianist to move arms and hands as though he has a third hand, at least a third hand. Fanfarinette, a “small braggart,” teases the listener to follow the music. La Triomphate is bolder. The Gavotte conclusion branches into six complex variations all with transparent sounds of the main theme. James M. Keller writes that this piece may show that Rameau kept up with Handel’s developments and plays can-you-top-this. Handel had five variations, but Rameau has six. The fast, occasionally explosive, thoughtful music ends by drifting away. Other selections on the program also end with sound disappearing, gently, but in the outskirts of sadness.

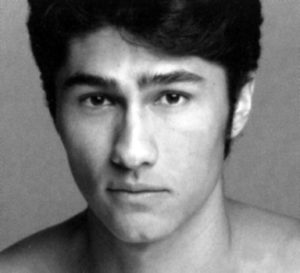

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote three piano sonatas between July and November, 1783, all published in Vienna. The Piano Sonata in F-major apparently is the last of the group. While it begins with a relatively quiet, inward facing Allegro, it grows and puts forth melodies that have dramatic qualities. The second movement, an Adagio, also begins in an understated way which becomes full of expression without abandoning Classical restraint. The closing movement, Allegro assai tosses its hat and flings surprises to the audience. Just when the listener thinks she knows how the composer is feeling about music and life, he turns on a dime and releases astonishing changes of direction. The fascination stops short of hypnotic due to the excitement which Mozart creates and delivers without any hints or preparation. Despite the energy of the movement, this music also quietly evaporates.

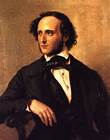

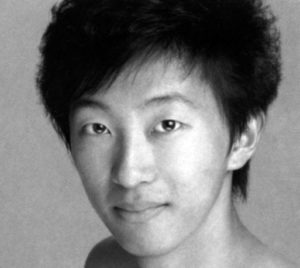

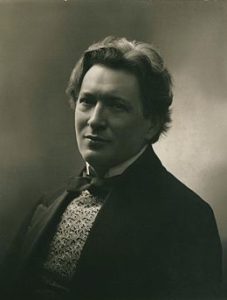

Felix Mendelssohn, composer (1809-1847)

Felix Mendelssohn, composer (1809-1847)

Felix Mendelssohn’s Variations Serieuses, Opus 54, is mind opening music. One may not take a break from listening; so much is happening in the brilliant piece. Yosemite Falls is a wonder. After rain or snow melt, the unbelievable happens: Yosemite Falls becomes even more impressive and inspiring. Mendelssohn’s twelve minute work is the musical Falls at its greatest. The fast rhythms become faster, daring the pianist and challenging the listener’s attention to sound. From sixteenth notes in the first variation, he moves to sextuplets, (Un poco piu animato –a little more animated)). Next there are staccato notes (Piu animato). More variations all filled by not one marvel of variation but it seems at least two at a time He finds syncopation, expressive passages; how many variations? eighteen. Each one is deeper in musical life developed and bursting with fire. Imagination on top of rhythm is woven into Time escaping, shaped by the composer’s call for poco a poco piu animato (little by little livelier and livelier). The super liveliness has seized Time, wound it higher into spirals of musical life which the composer, being an honest genius, then allows us to hear Time die away. It is another ending which drifts away like smoke, untraceable as life.

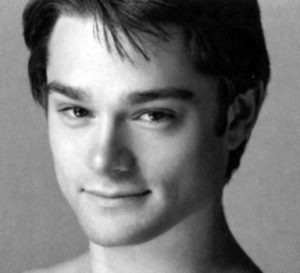

Daniil Trifonov, pianist

Daniil Trifonov, pianist

Through out the concert, Trifonov played with power, finesse, astounding speed, and still has ,heart left for expression. Part demon, part angel. He delicately caressed the keys in the Rameau as though he was bringing an inanimate thing to life. He may have channeled Mozart himself in the sonata. Trifonov did not shy away from taking Mozart’s Piano Sonata in F major that begins quietly into soaring, airborne changes of direction or altitude. As Rameau’s music was first for the harpsichord, could one state he was a master of the keyboards? I can imagine he was or he would not have written the Suite in A Minor. Both Mozart and Mendelssohn were known as master pianists, perhaps at a level above mere masters. Clara Schumann, renown as the star pianist of Europe before her marriage, wrote about Mendelssohn: “When all is said and done, he remains, for me, the most cherished pianist of all.”

Ludwig Van Beethoven, composer (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven, composer (1770-1827)

Now, there is the Hammerklavier. Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 29 in B-flat major is a world of mystery. Many consider it the most technically challenging of Beethoven’s piano sonatas; it is the longest, too. Its emotional life extends so far as one hears and feels in King Lear or experiences in an entire life. This writer/listener waited to write this brief account until she could listen to it again. The first movement, Allegro, is troubled, seems to dive into knots of thick ropes, climbs out, and then falls into more impediments: quick sand, rocky rubble, water that is deeper than it looks. Then, he, maybe it, stands up. The music finds him in a Scherzo which brightens the mood. It tries to play tricks on him, makes him jump over fallen branches, but he makes his way. It is not a jolly Scherzo, but it is Assai vivace (lively, vivacious enough) and travels away from the trials of the first movement Allegro. The third movement is a bleak ending though in the middle of the sonata’s life. Beethoven describes it Adagio sostenuto: Appassionato e con molto sentimento. It is sustained grieving, deeply felt and sounds like it cannot move forward, though this is the longest movement of any in Beethoven’s sonatas. It is nearly hopeless. It is nearly a prison cell without a window. It is beautiful but does not allow physical movement as imagined in the preceding movements. Feeling the passion of the Adagio, Beethoven will not abandon us, his listeners, or the spirit of his music. The final movement, Largo—Allegro risoluto (Fugo a tre voci) breaks away from the struggles, tricks, and grief of the other movements. Without an introduction we could notice, it leaps before us. Now there are windows and even a way into a garden. The music pays no more attention to the rigid ties it has left. How did it escape? It just took a step and, elated, revels in freedom.

The program began with Rameau’s Suite in A minor which includes Les Trois Mains and ends with Beethoven’s Fugo a tre voci, a fugue with three voices. The movement of hands and arms is so quick, crossing over, fingers flying that is looks like there must be more than two hands. The music is different, but supreme artists of the keyboard meet in their technique in this program. Rameau’s father was an organist; our composer, Rameau, was a music theorist and a professional organist until he was 49.

Mozart’s father was a violinist and “minor” composer. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart began to compose at age 5, beginning with the harpsichord. He was acknowledged to be one of the best pianists in Europe. Mendelssohn was a child prodigy, similar to Mozart. He showed ability very early and took his first piano lessons from his mother, Lea Solomon Mendelssohn. His intellectual achievements in language and drawing led to the twelve year old Felix meeting Goethe; they became friends. In this program, Daniil Trifonov has had an intimate conversation with great pianists. The audience has heard and seen a very great artist of our time.

The performance could not end. The audience, amazed by all it had heard, would not stop applauding until Trifonov gave them more. There were two encores, each a splendidly original choice, and each one by a uniquely great pianist. The first was I Cover the Waterfront, written by Johnny Green & Edward Heyman, and as played by Art Tatum.

Art Tatum, pianist

Art Tatum, pianist

Art Tatum was an astonishing pianist. His improvisations do everything; they will insert a new chord on each beat within one or two measures. Great pianists like Oscar Peterson and Bud Powell acknowledge Tatum’s influence. Few modern pianists would not adopt at least one of his “embellishments,” cascades of notes, rhythmic spurts, or weaving in and out of tempo. His “re-harmonization” of pop tunes became a regular practice among jazz musicians. This listener’s ears perked up when hearing the jazz sound of pop music from America’s ‘30s and 40s. Trifonov elegantly put on Art Tatum’s mantle. Fascination with the jazz chords and piling on of sounds took over.

Alexander Scriabin, composer (1872-1914)

Alexander Scriabin, composer (1872-1914)

More applause by the thrilled and greedy audience brought Trifonov back to play Scriabin’s Piano Sonata #3, the slow movement. Scriabin is known for his unique composition style now, but in the late 19th and early 20th centuries he was equally known as a virtuoso pianist. He performed in every important hall through Europe. One of his innovations was novel pedal effects. Trifonov brought Scriabin back as one of the greatest virtuoso pianists. Cheers for Trifonov’s presentation of the works of the towering pianists who came before him. The encores were a fitting homage to Tatum and Scriabin. Trifonov’s playing honored them all.

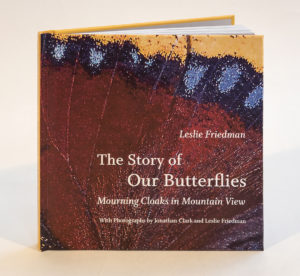

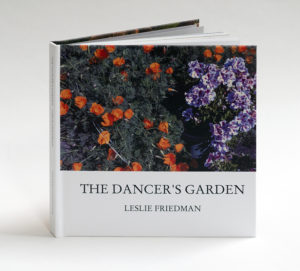

Remember that these two wonderful, LIvely Books are still on a special sale! Buy one book (of either book) and get 25% off. Buy two books (one of each or two of one) and the second book is half price. A great deal! AND, no postage payment from you. You cannot afford to pass it up. Each book has great VALENTINE value! Sale must end soon. More details on buying books: please see livelyfoundation.org/wordpress/?p=3890

Remember that these two wonderful, LIvely Books are still on a special sale! Buy one book (of either book) and get 25% off. Buy two books (one of each or two of one) and the second book is half price. A great deal! AND, no postage payment from you. You cannot afford to pass it up. Each book has great VALENTINE value! Sale must end soon. More details on buying books: please see livelyfoundation.org/wordpress/?p=3890

Sean Bennett – King of the Mice

Sean Bennett – King of the Mice Wei Wang – Nutcracker Prince, Grand Pas de Deux

Wei Wang – Nutcracker Prince, Grand Pas de Deux

Cavan

Cavan Sasha Mukhamedov – Sugar Plum Fairy

Sasha Mukhamedov – Sugar Plum Fairy Wona Park

Wona Park Johann Sebastian Bach, composer (1685-1750)

Johann Sebastian Bach, composer (1685-1750) Franz Schubert, composer, 1797-1828) (posthumous painting by R

Franz Schubert, composer, 1797-1828) (posthumous painting by R Daniil Trifonov, pianist

Daniil Trifonov, pianist Jean-Phil

Jean-Phil Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Felix Mendelssohn, composer (1809-1847)

Felix Mendelssohn, composer (1809-1847) Da

Da Ludwig Van Beethoven, co

Ludwig Van Beethoven, co

A

A

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms Fred Hersch, composer

Fred Hersch, composer

Franz Li

Franz Li

Es

Es