SF Symphony, Davies Hall, San Francisco, April 27, 2023: The program opened with Nautilus by Anna Meredith. Composed in 2011, this was its first SF Symphony performance. It is extremely challenging to write about this concert. When I think of this evening of music, I shake my head a bit and widen my eyes. Which superlatives are adequate? Joshua Bell was the soloist for Violin Concerto in D minor, Opus 47 (1905), by Jean Sibelius. Dalia Stasevska conducted. The SF Symphony performed Symphony No. 2 in D major, Opus 43 (1902), by Sibelius. Every moment of that music was powerful, urgent, necessary. Both of the Sibelius works sound like no other concerto or symphony. It was thrilling to hear and see this music. It was a stupendous, spectacular, over the top wonderful performance. Each SFS musician, Bell, and Stasevska were playing at the height of physical and mental experience. The Sibelius works are virtuosic masterpieces. The Violin Concerto demands the most intricate, masterful technique possible. Sibelius had dreams of becoming a violin virtuoso but instead moved further in his composing. The Concerto was written by someone who knew every bit of what a violin could do in the hands of a singular master; Joshua Bell is the person Sibelius dreamed of for this music.

Jean Sibelius, composer (1865 – 1957)

Jean Sibelius, composer (1865 – 1957)

The Concerto opens with a strong, almost other-worldly presentation that introduces the soloist’s amazing abilities with the relatively small instrument that is able to take the audience immediately into the sky as on a test jet, hum a lullaby, make our heads float on a cloud, and then brings us into a dark forest without a compass. Sibelius is not interested in comfort for the audience or the soloist. A cadenza, an improvisational passage played by the soloist or a written, fancifully decorated passage, usually comes as a climax. Sibelius was not interested in “usually.” A written cadenza is the heart of the first movement, Allegro moderato. The stamp of Virtuoso is pressed into every movement by the soloist. Joshua Bell absorbs the entire score into his physical being. It takes movement to make music, and, at the same time, the music which is created by movements then shapes the movements of the player. It is fascinating to see Mr. Bell express the music with each movement of his back, the hands manipulating the violin and bow, the step forward that happens when the energy of making music changes where the weight is placed in the body, and a foot comes down.

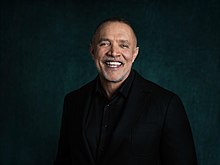

Joshua Bell, violinist

Joshua Bell, violinist

The second movement, Adagio di molto, is beautiful in a new way that Sibelius found to be beautiful. Sometimes it is the solo violin, sometimes the clarinet and bassoon, and then back to the soloist, a flute, the strings. All is quiet. It is a soft sensation. Was it because the music was soft to hear or was it making a softness the listener will remember as something one could touch or something that touched her? Allegro ma non tanto is the third movement. It has everything. It drives onward, it dances on beats we cannot count, flies and looks like it could crash, but it drives ahead and in spirals. Joshua Bell is unleashed – if there was ever the least restraint – as themes from throughout the Concerto propel this rocket. Sir Donald Tovey, the musicologist, composer, orchestra director, made that comment about a “polonaise for polar bears,” but he did not intend to demean Sibelius’ Violin Concerto at all. He also wrote: “… I have not met a more original, a more masterly, and a more exhilarating work than the Sibelius violin concerto.” The opening night audience, April 27, at Davies appropriately went wild applauding. After perhaps 4 (or 5) curtain calls, Mr. Bell appeared with his violin. He and Wyatt Underhill, the SFS Assistant Concertmaster, played an encore. Mr. Bell announced it as a little tune by Shostakovich. It was an excerpt from Shostakovich’s Five Pieces for Two Violins. It was a lovely, quiet beauty. The audience, giddy from getting an encore, applauded more and longer, but they had to be satisfied by the greatness they had already heard and seen.

In theater, actors are taught to listen to the other characters. One cannot rehearse lines in one’s head; that would set the actor apart from the action. I have a strong image of Mr. Bell waiting for his entries into the music. He is listening. He looks at the conductor. He is hearing it all and ready, completely occupied by the music. One time I saw him quickly pull a hair from his bow. He immediately returned to his focus.

There was a wonderful, silent communication between Dalia Stasevska and Joshua Bell. In one moment while he played, she faced him with her arms reaching out as though saying, “yes, yes, keep on just as you are.” Her gestures while conducting are strong, direct, clear. She shows the strength of her intent in every movement. Ms Stasevska is sought after by many orchestras mostly everywhere. She is the Chief Conductor of Lahti Symphony Orchestra, Artistic Director of the International Sibelius Festival, the Principal Guest Conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra. This season she performed with the Chicago, Toronto, Montreal Symphonies, the New York and Los Angeles Philharmonics.

The Symphony No. 2 in D minor, Opus 43 (1902) is another example of Sibelius’ grand, intelligent creativity. He wanted an abstract work designed so the music itself produces the music. Elements of the work seem to talk with other aspects of music and time. He supplied no story, no reference to Finnish folklore, and was not now even inspired by Finnish traditions. He stepped into the deep end and came up with something Sibelius that neither he nor others had thought of before. However, art is not always received by the onlooker or listener in the way the creator meant it to be. Finnish musicologists, audiences, and critics heard it as music for their resistance against Tsar Nicholas II. Finland was part of the Russian empire, but the Finns asserted their independence. When it had its premiere, Ilmari Krohn, Finnish critic, called this symphony “our liberation symphony.” Sibelius did not join in that description, but that mark has lasted.

Sibelius’s father passed away when Jean was only 3 years old. He and his mother moved to his widowed, maternal grandmother’s home. He was fortunate that he had a paternal uncle who was interested in music and gave him a violin at age 10. An aunt taught him to play the piano, but the violin was his first love. He and his brother and sister would play trios. Jean started composing short pieces and recorded them on paper. In 1883, on the subject of composing, he wrote, “They (his compositions) are rather poor, but it is nice to have something to do on a rainy day.” He was 18 at that time. When his Symphony No. 2 was premiered he wrote that “My Second Symphony is a confession of the soul.” The Symphony’s four movements all seem to grow from the first movement, Allegretto. it is like a family of four; they are not alike but one can see/hear their origins. The second movement, Tempo andante ma rubato, is totally different than the activity and continuous movement of the Allegretto. The SF Symphony was powerful, as inspired by Sibelius and led by Conductor Stasevska. The SFS never ran off the tracks though it moved through the different directions and meters like a train running in the air. The Andante was suddenly heart-rending, quiet, and full of longing. The last two movements, Vivacissimo–lento e soave and Allegro moderato bring all the passengers together, joined in a new reality. The music is the creator, peacemaker, and promise. The Finnish audiences were thrilled in 1902 just as we are in 2023. Their critics wrote it “exceeded even the boldest expectations,” Oskar Merikanto, composer. “An absolute masterpiece,” Evert Katila. Nothing less. A spectacular performance.

Dalia Stasevska

Dalia Stasevska

Wynton

Wynton  Wynton Marsalis (born 1961

Wynton Marsalis (born 1961 Outi Tarkiainen, composer

Outi Tarkiainen, composer Dmitri Shostakovich, composer (1906 – 1975)

Dmitri Shostakovich, composer (1906 – 1975)

Dame Jane Glover,

Dame Jane Glover,  George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) composer

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) composer Michael Tilson Thomas, Music Director Laureate

Michael Tilson Thomas, Music Director Laureate Gustav Mahler, born July

Gustav Mahler, born July  Clau

Clau

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

A

A

Benjamin Britten, composer, 1913-1976

Benjamin Britten, composer, 1913-1976 Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn

Clara Schumann (1819-1896)

Clara Schumann (1819-1896) Samuel

Samuel  Mich

Mich Conductor Xian Zhang

Conductor Xian Zhang