This article appeared in Our Neighborhoods: Mountain View and Los Altos, December, 2019, a magazine published by the Embarcadero Publishing Co., which publishes the Mountain View Voice, Palo Alto Weekly, Menlo-Atherton Almanac newspapers. Lively thanks Embarcadero Publishing for recognizing The Lively Foundation as a leader in creating community and selecting us to represent our community.

The first thing Leslie Friedman notices when she enters a room is the floor. Wooden? Concrete? Tiled? Her dancer’s eye is always looking for good floors for dancing. She is also always searching for ways her work can serve the community. She brings people together to dance, to enjoy dance, to learn about our many cultures, and about each other. Her dance succeeds at building community.

As an internationally touring performer, choreographer, and artistic director of the nonprofit Lively Foundation that operates in Old Mountain View, her deep passion for life and her art energizes her choreography and performances. She is first American dancer or artist of any kind to perform with joint sponsorship of the US State Department and host countries around the world. These “firsts” include performances in Moscow and Leningrad/St. Petersburg, Russia; Beijing, Shenyang, and Shanghai, China; Barcelona and Madrid, Spain; Warsaw, Lodz, Krakow, Poznan, Poland; New Delhi, Bengaluru (Bangalore), Kolkata (Calcutta), Chennai (Madras), India; Bucharest, Romania; Cairo and Alexandria, Egypt; Tunis, Tunisia, and more. Her performances in these cities plus London, Tokyo, Toronto, Seoul, were all given ovations and invitations to return.

She stirs up artistic presence on the Peninsula by inviting renowned dancers to teach and perform in the annual International Dance Festival@Silicon Valley that she hosts in Mountain View.

Artistic Director, Leslie Friedman

Artistic Director, Leslie Friedman

First launched in 2012, the week long festival seeks to create performance opportunities for professional dance artists, offers intensive training for dancers and dance students, and invites the whole community to experience dance in professional performance. “Some audience members would be dance lovers, for some it would be their first time watching, for all we hope to give them the excitement and beauty of dance,” says Leslie. The Festival also attracts adults aged 15 and up to classes in a wide variety of dances and exposes them to the new choreography created by the teaching artists. Performances and classes include traditional dances from many cultures flourishing in the Bay Area: Irish set dancing, Salsa, Polish folk dance, Mexican Folclorico, Afro-Haitian, several kinds of classical Indian dances, classical Chinese dance. These are in addition to Ballet, Tap, Line Dances, Contemporary, Jazz, and Ballroom dances.

Crystal Bella Chen and Oscar Adrian Rodriguez perform Ballroom dance in the International Dance Festival@Silicon Valley, 2019

Crystal Bella Chen and Oscar Adrian Rodriguez perform Ballroom dance in the International Dance Festival@Silicon Valley, 2019

“There is a rich variety of movement styles available for our open Master Classes on the Festival’s Full Day of Dance©,” says Leslie, “We encourage everyone to do what they love and also try something new.” All the classes are mixed levels. That includes beginners and pros.

“A ballerina will have an opportunity to learn Afro-Haitian Dance and love it as a beginner in the class. A complete beginner might have a wonderful time in Line dances or find a gift for Tap,” Friedman explains. “Professional dancers can showcase their work here. It gives them new audiences, a chance to demonstrate and develop their art.”

Through the IDF@SV, Friedman said she hopes to bring the diversity of arts of different origins while involving the community in dance. She also believes it is possible and important that everyone finds a way to move that they enjoy enough to keep doing.

“Move whatever moves, wiggle whatever wiggles,” she said. “If my work inspires someone to keep moving, wow!”

]ennifer Urmson, a mother of two boys, was happy to endorse the way Leslie Friedman and The Lively Foundation build community. She started taking Friedman’s weekly ballet classes when a friend invited her two years ago. “I had not been dancing for a very long time, and I was nervous about the idea of doing ballet as an adult,” Urmson said, adding that as a child, she was told ballet was for bodies of a certain shape. “But Leslie is wonderful as a teacher, very open and supportive. I was really pleased that after a couple of lessons, I felt myself getting stronger and improving my balance.”

Within Jennifer’s class there was a woman in her early 20s, other moms, and retirees. A few of them were organize activities for their dance class friends outside class, such as going together to attend a ballet performance at the Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts.

Urmson said whether you attend several classes or take part in a single workshop at the Festival, The Lively Foundation seems to have a way of connecting people.

“Months after the dance Festival, you’ll hear people exchanging highlights from the event when they run into one another around town,” she said. “Even if it’s just one class, you see a different side of people. You feel you know them better.” For more information about the International Dance Festival@Silicon Valley, contact livelyfoundation@sbcglobal.net

—Esther Young, 2019; photo of Leslie Friedman demonstrating a movement for Julie Van Gelder, private student and Festival participant, by Magali Gauthier

Shambhavi Dandekar

Shambhavi Dandekar

OTTAWA, ILLINOIS: 1967 Photographs by Jonathan Clark, published by Nazraeli Press. This award winning book presents photos of the small town the artist lived in for his first 10 years. He took the pictures when 15 years old. Like the Mozart of photography, his art was already outstanding. Ottawa still exists, but the way of life there is different. You will see a time that is gone in meaningful, beautiful photographs.

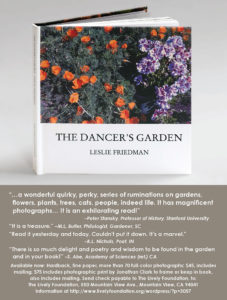

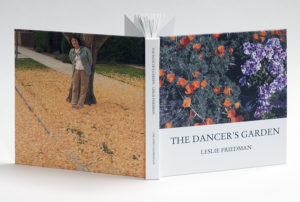

OTTAWA, ILLINOIS: 1967 Photographs by Jonathan Clark, published by Nazraeli Press. This award winning book presents photos of the small town the artist lived in for his first 10 years. He took the pictures when 15 years old. Like the Mozart of photography, his art was already outstanding. Ottawa still exists, but the way of life there is different. You will see a time that is gone in meaningful, beautiful photographs. THE DANCER’S GARDEN, This beautiful book has text and photos by Leslie Friedman with additional photos by artist Jonathan Clark and one by Dennis Parks, English actor. Review and comments on this book call it “a treasure,” “a marvel,” and “a wonderful quirky, perky series of ruminations on gardens, flowers, plants, trees, cats, people, indeed life. It has magnificent photographs…It is an exhilarating read!”

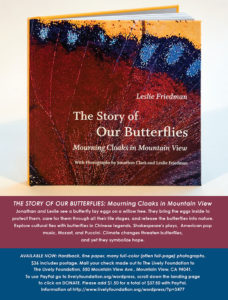

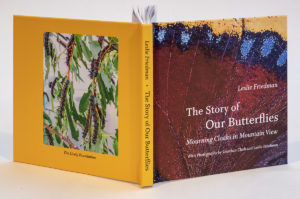

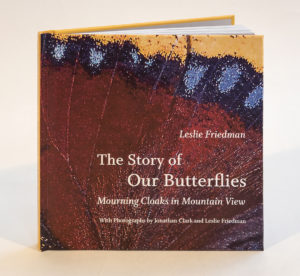

THE DANCER’S GARDEN, This beautiful book has text and photos by Leslie Friedman with additional photos by artist Jonathan Clark and one by Dennis Parks, English actor. Review and comments on this book call it “a treasure,” “a marvel,” and “a wonderful quirky, perky series of ruminations on gardens, flowers, plants, trees, cats, people, indeed life. It has magnificent photographs…It is an exhilarating read!” THE STORY OF OUR BUTTERFLIES: Mourning Cloaks in Mountain View, Text by Leslie Friedman with photos by Jonathan Clark and Leslie Friedman. Jonathan and Leslie see a butterfly lay eggs on a willow tree. They bring the eggs inside to protect them, care for them through all their life stages, and release the butterflies into nature. Explore cultural ties with butterflies in Chinese legends, Shakespeare’s plays, American pop music, Mozart and Puccini. Climate change threatens butterflies and yet they symbolize hope.

THE STORY OF OUR BUTTERFLIES: Mourning Cloaks in Mountain View, Text by Leslie Friedman with photos by Jonathan Clark and Leslie Friedman. Jonathan and Leslie see a butterfly lay eggs on a willow tree. They bring the eggs inside to protect them, care for them through all their life stages, and release the butterflies into nature. Explore cultural ties with butterflies in Chinese legends, Shakespeare’s plays, American pop music, Mozart and Puccini. Climate change threatens butterflies and yet they symbolize hope.

The Dancer’s Garden, published in 2019, is available from The Lively Foundation and the Stanford Bookstore.

The Dancer’s Garden, published in 2019, is available from The Lively Foundation and the Stanford Bookstore.

Readers from top L: Pam Wong (The Young One), Laurie Mokriski (The White Ethnic Dancer), Torey Bookstein (The Great One, and The Jive Person), Paul Harkness (The Old One), Jonathan Clark (The Film Guy), Susannah Wood (The Moderator).

Readers from top L: Pam Wong (The Young One), Laurie Mokriski (The White Ethnic Dancer), Torey Bookstein (The Great One, and The Jive Person), Paul Harkness (The Old One), Jonathan Clark (The Film Guy), Susannah Wood (The Moderator).

Artistic Director, Leslie Friedman

Artistic Director, Leslie Friedman Crystal Bella Chen and Oscar Adrian Rodriguez perform Ballroom dance in the International Dance Festival@Silicon Valley, 2019

Crystal Bella Chen and Oscar Adrian Rodriguez perform Ballroom dance in the International Dance Festival@Silicon Valley, 2019 Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)