Two days after the performance of Tchaikowsky’s Symphony #5, the tunes come back to my mind. Right now, it’s the gorgeous waltz from the third movement. I cannot put it out of my mind and really do not want it to go. Last night, it was the “Fate theme” that opens the symphony with an ominous, foot dragging rhythm. The late music writer, MIchael Steinberg called this the “Fate theme” because of an observation written by Tchaikowsky in his notebook as he began to compose this majestic work: ” Intr{oduction}. Complete resignation before Fate, or, which is the same, before the inscrut{able} predestination of Providence.”

Two days after the performance of Tchaikowsky’s Symphony #5, the tunes come back to my mind. Right now, it’s the gorgeous waltz from the third movement. I cannot put it out of my mind and really do not want it to go. Last night, it was the “Fate theme” that opens the symphony with an ominous, foot dragging rhythm. The late music writer, MIchael Steinberg called this the “Fate theme” because of an observation written by Tchaikowsky in his notebook as he began to compose this majestic work: ” Intr{oduction}. Complete resignation before Fate, or, which is the same, before the inscrut{able} predestination of Providence.”

Conductor Manfred Honeck led the San Francisco Symphony in a brilliant performance of Tchaikowsky’s 5th Symphony and Shostakovich’s Suite on Verses of Michelangelo Buonarroti, May 26, 2017.

Conductor Manfred Honeck led the San Francisco Symphony in a brilliant performance of Tchaikowsky’s 5th Symphony and Shostakovich’s Suite on Verses of Michelangelo Buonarroti, May 26, 2017.

Fate reappears to interrupt harshly the enchantment of the second movement. It wafts onto the dance floor to frighten the couples mesmerized by their waltz. In the end, after what may be violent struggles, Fate steps in and literally stops the music. Heart beats are suspended, breaths are held; the music begins again louder and faster, reaches its heroic climax, but is it a win by knock out for Fate? Or did the human step over the laws of gravity and predestination to become himself? I do not know. Troubled by that powerful yet ambiguous ending, late in the night I remembered Herman Hesse’s comment: “Your fate loves you.” Perhaps Tchaikowsky was wrestling with his angel. The SF Symphony audience rose to its feet, cheering each performer, the whole ensemble, and Maestro Honeck. Tchaikowsky knows how to make an orchestra expand its sound, express its melody with delicacy and verve, and give his listeners music that will possess them.

In the summer of 1974, Shostakovich received a book of poems written by Michelangelo. it was a gift from Shostakovich’s great friend, Leo Arnshtam. It was a year before the composer’s death. His health was ruined by cancer. He had had heart attacks eight years and three years earlier. He had had polio. He had been hounded through life by Stalin and his henchmen. At night, he would stand outside smoking so that when They came to take him away, They would not awaken his family. He kept composing, although he kept hidden some work which he knew would be controversial. Fortunately, the Soviet climate for culture was improving; unfortunately, it was happening late in the life of Dmitri Dmitrievcich, surely one of Russia’s most gifted composers and faithful sons.

In the summer of 1974, Shostakovich received a book of poems written by Michelangelo. it was a gift from Shostakovich’s great friend, Leo Arnshtam. It was a year before the composer’s death. His health was ruined by cancer. He had had heart attacks eight years and three years earlier. He had had polio. He had been hounded through life by Stalin and his henchmen. At night, he would stand outside smoking so that when They came to take him away, They would not awaken his family. He kept composing, although he kept hidden some work which he knew would be controversial. Fortunately, the Soviet climate for culture was improving; unfortunately, it was happening late in the life of Dmitri Dmitrievcich, surely one of Russia’s most gifted composers and faithful sons.

Shostakovich composed Suite on Verses of Michelangelo Buonarroti that summer. First, it was written for bass voice and piano. Then, he orchestrated it. The result opens the heart and mind of the listener. This was the SF Symphony’s first performance of the work. Baritone Matthias Goerne performed with them. He sang with sensitivity and understanding of the text and the music. His voice can be raspy or gentle; able to embrace the music when it is subtle or soaring. It was a performance which this listener will long remember. Maestro Honeck conducted with attention to each section of the songs and music. He is an active participant in the Symphony’s excellent music making.

Shostakovich selected eleven poems by Michelangelo. They express a variety of subjects which are part of Shostakovich’s life story as well as many life stories, especially of artists. They are: Truth, Morning, Love, Separation, Anger, Dante, To the Exile, Creativity, Night, Death, Immortality. The music also follows the arc of a life, beginning with an Adagio for Truth, then two Allegrettos for Morning and Love. Michelangelo was a Florentine. The great Florentine poet Dante had been exiled from the city two hundred years before Michelangelo remembered him in verse. Shostakovich knew what happens when the powerful confront an artist. There is economy in the music. Neither agony nor joy is overstated. Music does not muffle the voice or shunt it aside. The final verses lead to a surprise. Night, an Andante, and Death, an Adagio, take over Creativity‘s flowering energy. Immortality, the final verse, is rendered by Shostakovich as an Allegretto, a spritely vision dancing on a hilltop. Its simplicity and bright purity change everything.

Shostakovich selected eleven poems by Michelangelo. They express a variety of subjects which are part of Shostakovich’s life story as well as many life stories, especially of artists. They are: Truth, Morning, Love, Separation, Anger, Dante, To the Exile, Creativity, Night, Death, Immortality. The music also follows the arc of a life, beginning with an Adagio for Truth, then two Allegrettos for Morning and Love. Michelangelo was a Florentine. The great Florentine poet Dante had been exiled from the city two hundred years before Michelangelo remembered him in verse. Shostakovich knew what happens when the powerful confront an artist. There is economy in the music. Neither agony nor joy is overstated. Music does not muffle the voice or shunt it aside. The final verses lead to a surprise. Night, an Andante, and Death, an Adagio, take over Creativity‘s flowering energy. Immortality, the final verse, is rendered by Shostakovich as an Allegretto, a spritely vision dancing on a hilltop. Its simplicity and bright purity change everything.

Curiously, Shostakovich drew the melody of Immortality from something he had written when nine years old. Nothing was lost.

Curiously, Shostakovich drew the melody of Immortality from something he had written when nine years old. Nothing was lost.

Pictures, from top: Tchaikowsky, Manfred Honeck, Shostakovich, Michelangelo Buornarroti

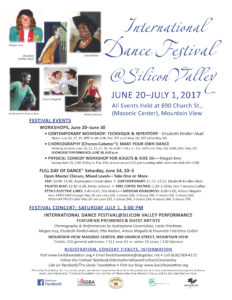

Arturo Magaña will perform on the Festival Concert, July 1st, 3 p.m. Mountain View Masonic Center, 890 Church St., Mountain View

Arturo Magaña will perform on the Festival Concert, July 1st, 3 p.m. Mountain View Masonic Center, 890 Church St., Mountain View

Audreyanne Delgado-Covarrubias

Audreyanne Delgado-Covarrubias Megan Ivey

Megan Ivey Elisabeth Kindler-Abali

Elisabeth Kindler-Abali Etta Walton

Etta Walton