Talking with Jasmine Jimison was a treat. I have seen her dance with the San Francisco Ballet in roles in The Nutcracker (Helgi Tomasson: choreographer) and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (George Balanchine: choreographer). Her onstage presence is a delight as she is able to embody roles as different as The Snow Queen and a wandering, love lorn lady lost in an enchanted forest in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Jasmine Jimison: Principal Dancer, San Francisco Ballet

Jasmine Jimison: Principal Dancer, San Francisco Ballet

She selected her life’s direction, stuck with it, worked hard, and now has arrived at the top of the top. Ms Jimison told me that she started out as a figure skater and began to study dance to help with her skating. Her skating teacher advised her to add the ballet movements, especially the arms, for her work on the ice. That was when she was “around 10 or 12.” The dancing gradually took over the skating. At 12 years old, she entered the SF Ballet School. She had started taking summer intensive programs at San Francisco Ballet and School of American Ballet, in New York, and others, but she stayed with the SFB school. A native of Palo Alto, she was happy to be near home.

Her family had no other dancers or artists of other kinds, but they were supportive in her training and career. I asked if her family was surprised by her dedication. The answer was no; they were “very supportive

Jasmine Jimison being promoted to Principal Dancer on stage after a performance of Ashton’s Marguerite and Armand // © San Francisco Ballet, photo by Lindsey Rallo

She loved figure skating and was very good at it, but even at the young age of making big decisions, her decision was practical. Jasmine said that figure skating is a short career, skaters stop at 15 or, if lucky, maybe 20. Compared to that, ballet, notorious for the brevity of a dancer’s career, seems like a long, life time career.

Ms Jimison has helpful suggestions for young dancers and not so young dancers. She said that “Everyone has a unique time line for training and dancing. The old rules that a person cannot start to dance seriously after 12 years old are no longer in place. So much depends on the individual’s efforts and the quality of training.” In addition to studying at the SFB, Jasmine studied privately with Kristine Elliot – a beautiful dancer, soloist in the American Ballet Theater. Ms Elliot gave Jasmine significant training. Jasmine feels certain that being in one on one classes with Ms. Elliot gave her a significant boost in learning.

A recent thrill for SF audiences and for Ms Jimison was her role as Odette/Odile in Swan Lake. Jasmine said being cast in the double role is usually set on “veteran” ballerinas with great experience. However, the new Principal Dancer was given the role. Odette, the good princess, was turned into a swan by the evil wizard, Von Rothbart. Odile, the bad “princess,” daughter of Von Rothbart, puts a spell on Prince Siegfried. The Prince had fallen in love with Odette by the romantic Swan Lake. In the picture below, she is Odette.

I asked Jasmine if she preferred one of the parts. She thought that Odette’s personality was closer to hers, it felt more natural, but it is exciting to delve into characteristics that are completely different.

She has appeared in many different roles but she said that Juliet is her favorite, so far. She likes knowing that the audience understands the feelings of the characters. That means that they are with Juliet as she goes through so many challenges. Also, the music is wonderful. It is the “most important in shaping the quality of the movement.”

She will not know what ballets or roles she will be in until much closer to the season. She is now learning Grosse Fugue and will learn Clemence in Raymonda. The San Francisco Ballet will go on tour to Madrid, October 1st. Ms Jasmine Jimison, Principal Dancer, is excited about the company’s first international tour with her. I asked her what it is about dance that drew her in to make it the center of her life. She answered that she loves the physical aspect of it, but it also gives her a way of expressing herself and the feelings from the music and characters. She said that these were things she could not express verbally. However, she expressed herself clearly and articulately in our conversation just like the clarity and meaning she puts into her dance.

Photographs compliments of the San Francisco Ballet.

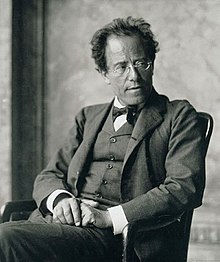

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony.

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony.