The program for this recital on Sunday evening, January 22, began with unfamiliar works by Alexander Vustin, Lamento (1974); Leos janacek, Piano Sonata, 1.X.1905 (1905); Valentyn Silvestrov, Bagatelle, Opus 1, no.3 (2005). After the first three came Ludwig Van Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 31 in A-flat major, Opus 110 (1821). Was this a reward for the audience which had to pay attention to three new-to-most solo piano works? Not exactly, though one could tell it was Beethoven coming into Davies Symphony Hall as soon as this extraordinary, great artist touched the first keys. Andsnes had looked deeply into Beethoven’s dual vision of happy and something different than happy that propels our lives.

While the first pieces were completely different musically, they shared a background and emotion: each one had been inspired by an act of resistance to a realm of political oppression. Andsnes quotes Vustin writing “aspects, such as style, material, dynamics, tone color and “emotional” character, are of secondary importance. The law which governs musical time may be expressed in numerical terms.” And, yet Lamento is a delicate, deeply felt and purely heard emotion in music. The composer attended a friend’s funeral; a bird sang throughout the event. The bird song plays simultaneously in opposition to the sadness. Though very brief, this music is a heart’s response to the tyranny of death and the tyranny of the Russian control of life. Andsnes comments in his program notes that seeing Vustin at the Rosendal Chamber Music Festival, founded by Andsnes, was a moving experience. He could see Vustin’s reactions to freedom of art in Norway, especially when listening to the music of Shostakovich.

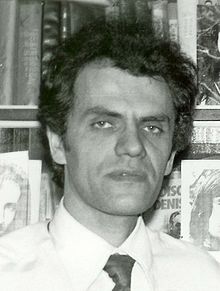

Alexander Vustin, Composer (1943-2020)

Alexander Vustin, Composer (1943-2020)

Leos Janacek created his Piano Sonata, 1.X.1905 in reaction to the death of 20 year old Frantisek Pavlik, a Moravian who was participating in a protest. He was stabbed by a bayonet. Janacek was a Moravian. Where is or was Moravia? It has an ancient history as a major, medieval kingdom, Great Moravia. Going back into the 4th century, it was populated by Celtic and Germanic tribes. Poland, Hungary, and Bohemia all wanted its land; it was independent until became incorporated into the Kingdom of Bohemia. In 1526, the Austrian King, Ferdinand–he became Ferdinand I of the Holy Roman Empire–claimed it. Moravia became part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. After World War I, the map changed. Moravia and Bohemia became parts of Czechoslovakia. The region’s communities included Czechs speaking Czech language and Germans speaking German. Moravians within the Czech community were a minority. The troubles that led to Frantisek Pavlik’s death were over the Czech speaking population’s desire to have a university using their language. German speaking Moravians opposed it. Differences were settled, but not before Pavlik’s death.

Leos Janacek (1854-1928) with his wife, Zdenka, 1881.

Leos Janacek (1854-1928) with his wife, Zdenka, 1881.

Janacek had many career pursuits. One was collecting and publishing Moravian folk music. His first big success as a composer was the premiere of his opera, Jenufa, in Brno. The opera was set in Moravia, and the home town music lovers gave it great support. This Sonata brought attention to Pavlik, a carpenter’s apprentice. By writing music in his memory, Janacek embraced him as a folk hero to be added to the Moravian consciousness of their identity and long history. Leif Ove Andsnes did not stand up between the first pieces on his concert. Instead, he waited in silence before beginning the next music. One could sense the intensity of Andsnes’ feeling for the oppressed and those who resist.

Valentyn Silvestrov, born 1937, Kyiv, Ukraine,

Valentyn Silvestrov, born 1937, Kyiv, Ukraine,

Before 2022, many Americans may have known as little about Ukraine as they might have known about Moravia. Russia’s invasion in February, 2022, changed that. The war is in headlines daily; many, many thousands have died; millions have become refugees. Valentyn Silvestrov, born 1937, in Kyiv (previously known as Kiev) escaped the war at age 85. He now lives in Berlin. Andsnes gave Silvestrov’s Bagatelle, Opus 1, no. 3 the expert treatment it deserves. The Russian establishment did not approve of Silvestrov’s style when he was a conservatory student. Instead of capitulating to fit in, he retreated into his private life and began writing music that pleased him. It was a nearly Romantic style. Judging from this composition, his music is sensitive and expressive. He wrote, “I do not write new music. My music is a response to send an echo of what already exists.” This does not mean it is not original. It means he writes music. It has been called post-modern and neo-classical. It is music and really does not need a pigeon hole. Silvestrov’s music has emotion, drama, and delicacy. I was surprised and delighted to hear the Bagatelle take us to a brief moment of the blues. The melody picked up the audience like the breeze lifts a boat gliding along a lake. Silvestrov stated that his music is “Not a philosophy, not a system of beliefs, but the song of the world about itself, and at the same time a musical testament to existence.” Silvestrov’s opposition to the invaders of his country can be found in his music. His choral work, Diptych, 2014, expresses patriotism and is dedicated to Serhly Nigoyan, an Armenian-Ukrainian killed in 2014, the beginning of the current catastrophe. The music is for the 1845 poem, Testament, written by Taras Shevchenko.

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Leif Ove Andsnes paused after playing Silvestrov’s Bagatelle and then changed the world of sound with Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 31 in A-flat major, Opus 110. It is shorter than other sonatas and on first impression, it seems to be so pleasant. It is pleasant, but there is more. The first movement is Moderato cantabile molto expressivo; it sings. We have lyrical charm. Beethoven was a nature lover; in this movement one might almost see a green hillside and daffodils. I wanted to write we might see him skipping in the park, but that is not moderato. It is a delight. Where is it going? The second movement is a scherzo Allegro molto. Now we have still more movement and more bright, happy harmonies. There are playful folk songs. This music takes us away from Beethoven’s real world: Napoleonic Wars, blindness, chronic illness. He and we are taking time to breathe, to relish being alive. The last two movements are played without a break. Now Beethoven gives us life in the round. Sadness flows over us. Our thoughts are serious but cannot find the remedy for sorrows. The third movement is Adagio ma non troppo; we go slowly into the experiences and feelings which stretch us and can dominate us with regret and even pain. The last movement, Fuga: Allegro ma non troppo, lets us rise up but not too much. We will see beyond today’s pain. The music, so beautiful, ascends gently. Somehow, we are alive and grateful to be so.

Poetic Tone Pictures, Opus 85, by Dvorak, is a surprise. It is Dvorak music for solo piano, a rare phenomenon. Leif Ove Andsnes has made it a mission to perform this wonderful series of brief, expressive pieces. Andsnes says it is “the great forgotten cycle of 19th century piano music.” It is definitely a great experience to be able to hear 13 Dvorak pieces. Each one is about 5 minutes, has a title, as Dvorak described them in a letter, and each one is a Tone Picture of places, seasons, emotions. There is Twilight Way, In the Old Castle, Reverie, Goblins’ Dance, Bacchanalia, On the Holy Mountain. And, that’s only six. It was fascinating, touching, and even entertaining. The variety of musical structures combined with expressive emotion and evocative style was a rich musical experience. The audience fully appreciated the Poetic Tone Pictures; they jumped from their seats and gave Leif Ove Andsnes at least 5 curtain calls.

Andsnes acknowledged the thrilling response from the audience with two encores. The second one happened because after the first the non-stop applause continued without a pause. His first selection was Ballade of Revolt, by Norwegian composer Harald Saeverud. This music of struggle begins quietly and ends in an avalanche of refusal to bend to oppression. It had an enormous impact. Andsnes closed with Chopin’s Mazurka, Opus 30, No. 4. Chopin’s mazurkas are at the heart of Polish culture. The Poles, dominated by Nazi Germany and then by Soviet Russia, struggled to stay anchored in their culture. Leif Ove Andsnes kept true to the theme he projected through the first pieces on his program. He is a brilliant, extraordinary artist.

Antonin Dvorak (18411904)

Antonin Dvorak (18411904)