November 16th at Davies Symphony Hall we heard majestic music performed by the San Francisco Symphony; the totally amazing pianist, Helene Grimaud; the SF Symphony Chorus with soloists Liv Redpath, soprano, and Michael Sumuel, bass-baritone.

Liv Redpath, Soprano soloist

Liv Redpath, Soprano soloist

Entwine Dai Fujikura was asked to create a five minute piece for orchestra. The theme was the current world situation: the Covid pandemic. While considering what the pandemic did to ordinary lives: isolation, fear of getting it from someone, avoiding crowds – what struck him first was “touch.” Do not touch was pressed forward from childhood to adult minds. Fujikura, one of the foremost contemporary Japanese composers, presented a fascinating piece. One of its characteristics is the music being passed along from instrument to instrument. Powerful, repetitive sounds from the strings are also highlighted by light harmonics sometimes flickering in and out beyond our constant hearing. The human touch was what we needed and could not have. Fujikura gave us an original approach to sound.

Maurice Ravel, composer (1875 – 1937)

Piano Concerto in G Major Ravel was into jazz. He managed to stretch sounds and rhythms into completely new and always exciting music. If you have not heard this Concerto, look for it and be there. It is inventive and alluring and will wake up your head, even if you did not know that you were sleeping. Ravel toured in the USA in 1928. He heard American jazz, met Gershwin – he asked to study with Ravel but Ravel said no – and came home to France. He worked on this Concerto from 1929-1931. He was writing Concerto in D Major for left hand at the same time. The extraordinary Helene Grimaud played the Concerto like it had been written for her.

She managed the ins and outs of the music which skids along from crazy wild music speeding away with it to the second movement, Adagio essai, which becomes slow and quiet. Grimaud was fantastic in the Adagio. The notes seemed to be separated farther than normal but they never went away. The left hand has a waltz to play continually. Then the orchestra re-enters, and high spirits and exuberance take over. There are unusual breaks and emphasis on unexpected notes. It is a very special Concerto composed by a unique composer and played by a very special pianist. Let the music jump! Glory time.

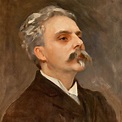

Gabriel Fauré, composer (1845-1924)

Gabriel Fauré, composer (1845-1924)

Requiem, Opus 48 Gabriel Fauré was the choirmaster at La Madeleine Church in Paris beginning in 1877 and then became organiste titulaire serving in that esteemed position for nine years. His Requiem, the Mass for the Dead, was performed first at La Madeleine. Despite his excellent and long service, he did not like the music which was allowed for churches. He began work on a Requiem soon after his father’s death. He added work to it for two years without ever saying that it was for his father. In a strange coincidence, his mother passed away only two weeks before the Requiem’s debut. He loved his parents and felt the losses. Still, he was not enthusiastic about the orthodox Catholicism. In 1902, Fauré said,

“Perhaps instinctively I sought to break loose from conventions. I’ve been accompanying burial services at the organ for so long now! I’ve had it up to here with all that. I wanted to do something else.”*

And he did. By editing the “normal” Requiem verses, leaving out the most terrorizing words of damnation, his Requiem reached out to suffering loved ones as well as to the one who had passed away.

“People have said my Requiem did not express the terror of death; someone called it a ‘lullaby of death.’ But that’s the way I perceive death: as a happy release, an aspiration to the happiness of beyond rather than a grievous passage.”*

The San Francisco Symphony Chorus and the soloists were superb. The sopranos lift the spirit singing on C for two measures. The tenors, as described by Ron Gallman, “unfurl a long melody, chant-like in its purity and simplicity.”* The baritone soloist in the Offertorium projects a glowing, mellow sound that floats over the orchestra. The soprano solo shines in the Pie Jesu. She is calm and hopeful for the lost beloved.

Although Fauré left some of the texts out, it was still useful for Catholic funerals. He did not include the Dies irae, the Last Judgment. He kept brief, though to the point, passages; from the Offertorium: “free the souls of the dead/from hell’s punishments and the fathomless void” After the Sanctus: Holy, holy, holy Lord God of Hosts./ Heaven and earth are full of your glory./ Hosanna in the highest” he goes to Pie Jesu: “Holy Jesus, Lord,/ give them rest. Give them rest, eternal rest.”

Through the entire Requiem, Fauré makes light/lux and rest eternal/requiem aeternam the central message of his beautiful vision. He adds verses from the Libera me/Free me, and, briefly, lines from Dies irae in Libera me. The harsh “day of wrath/ calamity and misery;/that day, that day is momentous/and exceedingly bitter.” contrasts with peace. Fauré returns to peace, stays with peace, gives us music and song of peace.

*Quotations from Fauré, and one from himself, are from Ron Gallman’s program note essay.

Helene Grimaud

Helene Grimaud