Violinist Joshua Bell’s recital at SF Symphony’s Davies Hall, Sunday, December 11, was astounding. With pianist Peter Dugan, Mr. Bell gave us the musical equivalent of a home run with the bases loaded. It was a stunning performance from every perspective: the program selections, the perfection of sound, the integration of violin and piano, the physical presence of Mr. Bell. What have I left out? If there is something missing from that list it is only because I am still envisioning the performance, and it is still breathtaking.

Violinist Joshua Bell’s recital at SF Symphony’s Davies Hall, Sunday, December 11, was astounding. With pianist Peter Dugan, Mr. Bell gave us the musical equivalent of a home run with the bases loaded. It was a stunning performance from every perspective: the program selections, the perfection of sound, the integration of violin and piano, the physical presence of Mr. Bell. What have I left out? If there is something missing from that list it is only because I am still envisioning the performance, and it is still breathtaking.

Ludwig Van Beethoven ( 1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven ( 1770-1827)

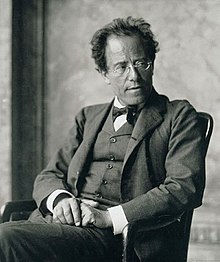

Since he is so well known, one might imagine the program Mr. Bell would perform would be familiar; instead he presented works that neither I nor the Hedgehog pianist and bass baritone knew. The opening work was a brilliant curtain raiser: Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Major, Opus 12, no. 2. It was composed in 1797 or 1798 and published in January, 1799. It was a daring, innovative composition. The two instruments are equally featured and truly “play well together,” as a school report sent home might declare. Mr. Bell’s physical movements express the music and also gave him opportunities to turn toward the pianist and physically, visibly demonstrate their relationship. They were not playing the same notes or rhythm but interlacing each instrument’s music to make the music of the sonata. It was a delightful work from the engaging beginning to the middle section’s nostalgic, nearly despairing sound, and the final Allegro suggesting all is well — for the moment.

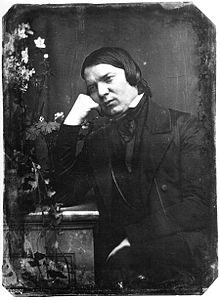

Robert Schumann’s Sonata No. 2 in D minor, Opus 121 is a hurricane of sound, a stage 4 emotional storm. While the music could be said to crash like the ocean under the hurricane, the composer does not lose his way with his creation. He is in control of his ship. Schumann composed it in 1851, a year of tremendous productivity. He completed 18 works in that year, reworked his Symphony No. 4, plus three overtures, a piano trio, works for piano and violin, lieders; it is an amazing year. Early in 1854, he attempted suicide by jumping into the Rhine. He died in 1856, in an asylum in Bonn. Fortunately for him and us, he was able to create great works before the internal storms incapacitated him. This work also was a new sound for the Hedgehogs. It kept the audience leaning forward, awaiting the next tumult. Despite my descriptions of the Sonata as a hurricane, the work is not a single dimension. There is a graceful lyricism in the first movement and the third, Andante, has a touch of happiness. In all, the Sonata ends by turning toward a hopeful moment. This is an extraordinary way to experience Schumann’s depth.

The page for this recital in the program book shows in very small print, “Additional works will be announced from the stage.” Just seeing that one line created a thrill of expectation. In the second half of the performance, the personable, at ease Mr. Bell shone as he took a microphone to introduce the next pieces. It was remarkable to see his relaxed personality apparently talking with each person in the audience though he was talking to thousands of us.

The second half was to begin with Claude Debussy’s Violin Sonata in G minor (1917). It was another splendid selection which I do not think I had ever heard. I am grateful to Mr. Bell for choosing it. Debussy was suffering terminal cancer when he wrote it. He worked on it in 1916, put it aside, and finished it in 1917. It is a culmination of the beauties that one hears in Debussy’s music. It demonstrates how strong and lasting something transparent, light, and gentle can be. It could be light in terms of weight but also music as light; it is a real thing which one cannot ever touch. Debussy performed its premiere in Paris, May, 1917, and passed away less than a year later. Although the Debussy was the only work listed for the second half, Mr. Bell and Mr. Dugan actually began with Nigun from Baal Schem Suite by Ernst Bloch. When he introduced the piece, Mr. Bell noted that Bloch was Jewish and, since Chanukah was only a week away, he was proud to present it. He paused exactly the right number of moments and then commented that Ye probably was not in the audience. Albert Camus reflected on the political essence of art; it was a completely justifiable addition to the Joshua Bell and Peter Dugan performance. The music was stunning; original and also embodying tradition, ways of living, ways of surviving. Nigun is said to be a pleading with heaven; Bell and Dugan achieved the effect of reaching deeply into one’s being. Bloch was Swiss, came to the US in 1916, became the Music Director of the Cleveland Institute of Music, then the Director of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and joined the faculty of UC, Berkeley. This Nigun was a marvelous reunion of Bloch and the Bay Area.

One more addition to the program was Bartok’s Rhapsody No. 1. None of these additions were brief or light weight. The Bartok work and the Bloch and the Debussy all existed in different worlds of sound, rhythm, emotion. As one might expect the Bartok piece activated the strange music of the Romanian/Hungarian folk tunes and dances, but that does not mean that the music was as expected. Each section was diverse within the whole and each section had the wild heart of the villages stirring souls and hearing this wildness. Both musicians became completely someone else in each of these remarkable, peak performances. It was an amazing thing to see as well as to hear: a transformation and a musical life in perhaps ten minutes.

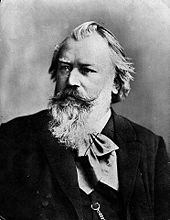

Those pieces were considered part of the program. Then, there were the encores! We all must find out what Joshua Bell eats for breakfast and whether he and Peter Dugan prefer running or swimming. The focus of the performers and their energy was amazing. The first encore was Clara Schumann’s Romance #1. Clara Wieck Schumann, married to Robert Schumann with whom she had nine children, was recognized as the finest pianist in Europe. They fell in love when very young. Her father did not approve, but they married. This Romance is one of three, Romances, all fine compositions. This writer has heard it on a cd and on the radio, but it never touched me until hearing it not only live but performed by Bell and Dugan. It is graceful with an underlying power; the performance was eye opening, reminding the listener what Clara Schumann, who toured her performances across Europe, could do if she had had more time to write.

Scherzo-Tarantella by Henryk Wieniawski was the opposite of Clara Schumann’s Romance#1. This was fast and then even faster. It was a mad dance taking its name from the motions of one bitten by a tarantula. Another fantastic, seldom if ever heard piece, this one sent the giddy audience up to the roof top and down again. After sitting for a couple of hours, I believe everyone present felt sure in their nerves and blood that they could prance, run, leap for however much time and music they could have. This concert was beautiful, powerful, and world moving.

Claude Debussy (1862-1918

Claude Debussy (1862-1918

Clara Schumann (1819-1896)

Clara Schumann (1819-1896)

Yuja

Yuja

Hector Berlioz (1801-1869) French

Hector Berlioz (1801-1869) French

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) French

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) French Yefim Bronfman

Yefim Bronfman

Alexander Borodin

Alexander Borodin

Jean Sibelius, 1913

Jean Sibelius, 1913