Igor Levit, the astonishing, internationally celebrated pianist, came to San Francisco for a two week residency with the San Francisco Symphony. He performed four different programs plus an open rehearsal. The last of the four was a recital with surprises throughout. It added up to eight performances. Each one was remarkable for Levit’s brilliance as a pianist, his deep knowledge of the repertoire, and his musical choices. The Hedgehogs attended three of the four: all Beethoven, June 17; Busoni’s immense piano concerto, June 22; a recital with works by Brahms, Fred Hersch, Wagner, and Liszt, June 27. We were unable to hear the chamber music concert with members of the SFS. It must have been very fine, but our three musical banquets were quite filling for hearing, seeing, and thinking. In fact, they were also entertaining. This is the first of three articles about Igor Levit’s performances.

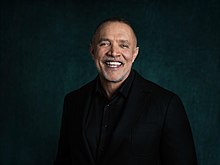

Igor Levit describes himself as “Citizen. European. Pianist.”

Igor Levit describes himself as “Citizen. European. Pianist.”

The first concert series offered two of the most well known Beethoven masterpieces: the Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major, Opus 73, called Emperor (1809), and the Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Opus 55, Eroica (1803). It was good to start our experience with Levit with music that is grand, complex, inventive and which we have heard before. I am not suggesting one could hum along, only that a listener’s memory might be able to imagine what Levit was doing with these landmarks of Western civilization.

He climbed inside the music. His partnership with the SF Symphony was a great match. The SFS, conducted by Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen, played with strength and truth. It was not backing up the Visiting Artist; they were partners in creating their understanding of Beethoven’s music. As Levit stated in an interview with Corinna da Fonseca-Wolfheim in the SFS program book, “my goal is not to sound like Beethoven. What I do all day long is try to understand, why did Beethoven decide to write a piece this way and not the other way? But at the end of the day, I’m the one who plays it, not him. So, the goal is kind of to have it both ways.”

The “Emperor” concerto premiered, in 1809. Musicologists have considered it the apex or fulfillment of Beethoven’s “heroic era,” though this concerto came a year after the 1802-1808 noted as an era of prodigious creativity. Beethoven found a totally original way to open the concerto. The stunning beginning would awaken the audience to the realization that they were experiencing music presented in a new way, and they would need to listen in a new way, too.

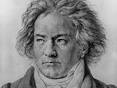

Ludwig Van Beethoven, Composer (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven, Composer (1770-1827)

The first movement is the longest Beethoven wrote. It is inventive in every facet. Curiously, it is the increasing presence of dissonance that serves as an audio seasoning and builds excitement. Beethoven then brings in quiet moments which stand out even more in contrast with the vigorous new movement. Levit let the Adagio un poco mosso run right into the final movement, Rondo: Allegro ma non troppo which became a frequent way to perform this concerto. The first movement is very long; this combination balances the music in real time. It spurs the music audibly onward and upward. The slower movement presents two chorales; first one for the piano, and then one in the orchestra. There is just a slight change of rhythm in the piano’s accompaniment. Being slightly off of the orchestra’s rhythm focuses the piano carrying the melody.

As Beethoven rounds the course he created for himself and the “Emperor,” he allows a breath of silence and lowers the pitch of the music. The finale allows a new theme to take a powerful bow in the appropriate tempo. Now, a Beethoven special: a romping German folk dance. The timpani takes over in another quiet moment, and there is an enormous burst of bright stars at the end.

Watching Levit perform is nearly so interesting as hearing him play. Fortunately, his quirks do not go on long enough to take attention away from the glorious music he makes. His first gesture was to hold up his left arm high and a little to the left with palm up but not flatly up. It seemed to express “there we are,” or maybe “this is the music right here.” His gestures and looks were often related to the music and his partners, Conductor Salonen and the SFS. He looked at the orchestra players either to acknowledge their playing or perhaps to send a mental message. He turned his head to see Salonen. Occasionally, he looked out to the audience and up to the audience in the choir loft as well. He leaned back to stretch his legs under the piano. Although one Bay Area writer observed that Levit was doing these motions because he felt so good about being in San Francisco, I saw him do the same exercises/expressions/quirks in a video of him performing the “Emperor” at the 2020 Nobel prize concert. It is him. Why would he pretend?

After many, many curtain calls, Igor Levit played one of Felix Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words, Opus 30, “Consolation.” It was calming, quiet, heartfelt, beautiful. The audience, gasping, cheering, and applauding kept clapping, but he was gone for now. Mr. Levit’s residency was off to a tremendous start

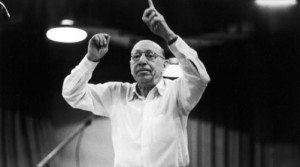

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony.

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony.

The San Francisco Symphony was stellar and brilliant performing the “Eroica.” Music Director/Conductor Salonen kept the orchestra in carefully ordered form. This symphony is written so that the audience cannot anticipate what will happen next in the music. Even though the “Eroica” keeps the classical form of four movements, what Beethoven does within the form is new. The second movement, “Marcia funebre: Adagio assai,” has the funereal feeling and pace. While this Symphony No. 3 was composed, Europe was on fire with revolutions and imperial wars. There would be many military burials and also soldiers with dire injuries visible in all towns. Conductor Salonen did not let the music sit in sadness. He kept it active and alive, as much the march, not only a funeral. That approach meant that it was not a huge departure when the third movement, Scherzo: Allegro vivace, rushes on the scene. The music propels itself as though on quickly moving feet. At the final movement, the theme splits itself in two directions which grow into twelve variations. Multiple layers of music and multiple actions make an amazingly full, lively world. This is where Beethoven meant to go. The audience was treated to a fresh, exciting, Symphony No. 3. Salonen and the SFS made it new.

Samuel

Samuel  Mich

Mich Conductor Xian Zhang

Conductor Xian Zhang

from left: Beethoven, Herbert Blomstedt, Garrick Ohlsson

from left: Beethoven, Herbert Blomstedt, Garrick Ohlsson

Emanuel Ax

Emanuel Ax

Wolfgang Amadeo Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeo Mozart Arnold Schoenberg, photograph by Man Ray

Arnold Schoenberg, photograph by Man Ray Medieval woodcut of trickster, Tilll Eulenspiegel, courtesy, San Franciso Symphony

Medieval woodcut of trickster, Tilll Eulenspiegel, courtesy, San Franciso Symphony Itzhak Perlman

Itzhak Perlman Rohan de Silva

Rohan de Silva