Part II: A FAIRY TALE OPERA

When the French author, Charles Perrault, published his story Barbe-bleu/Blue Beard, 1697, themes from the story had appeared in the 15thc. The themes included serial murders of wives and the importance for young women to obey their husbands in all details. When Bela Bartok decided that writing an opera would give his reputation a lift, he chose Bluebeard. It was to be his first and only opera. He wrote it in 1911 and entered it in a competition for a one act opera. It was refused. He offered it to the Hungarian National Opera; they also dismissed it as impossible to stage.

Bartok returned to his ethnomusicology researching music in Hungary’s forests and villages. During World War I, he returned to composing. The Hungarian National Opera asked Bartok for a ballet; it was The Wooden Prince. It debuted in 1917 and was a great success. After the warm reception for the ballet, the HNO made a double bill by adding Duke Bluebeard’s Castle. Unfortunately, it had mixed reviews. It was, after all, a very dark story.

This was an era that sought knowledge of human psychology and brought forth theories of the unconscious. Sigmund Freund published Totem and Taboo, 1913. Carl Jung’s Psychology of the Unconscious appeared in 1912. Symbolism was a popular trend in literature and music. Debussy composed an opera of Maerterlinck’s Pelias et Melisande.The Barbe-bleu story inspired Maeterlinck’s play, Arione et Barbe-bleu

The performance, at Davies Symphony Hall, March 3rd, began with narration spoken by actor Breezy Leigh. Her introduction suggests that the strange story might be inside of the listeners. It never was a history; it may be a struggle in our psyches.

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director of the SF Symphony, Conducts Duke Bluebeard’s Castle with singers Michelle DeYoung and Gerald Finley.

Despite the grim, gory story, maybe because of those aspects, the music and singing completely captured our attention. The singers became the characters. Mezzo-soprano, Michelle DeYoung, as Judith truly projected the new wife’s innocence, curiosity, proud demands she made of her host. Ms DeYoung’s voice was well suited to the emotions rebounding from happy to terrified. Gerald Finley, bass-baritone as Duke Bluebeard was splendid and horrible as the master of the Castle and keeper of his wives. SF Symphony’s Music Director, Esa-Pekka Salonen, conducted the orchestra and singers with a deep understanding of mysteries contained in Bartok’s opera. He kept faith with Bartok.

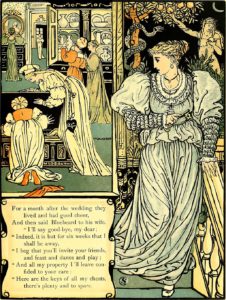

This story is different from the Perrault tale. In Perrault’s, there are 6 wives, all dead, and hanging from hooks on the walls of an underground chamber flooded with blood. I remember that image from long ago when I read the story. The young wife is not given a name. Duke Bluebeard marries the younger sister of a neighbor family, leaves his castle, gives the new wife the keys. He warns her not to go into the chamber. She invites her relatives and friends to a party at the Castle. While the party continues, she sneaks away to open that chamber. She runs away from the bloody scene, dropping the key for that room. It is stained with blood that will not wash off. Duke Bluebeard returns, sees the key, and threatens to kill her, but his new wife asks for a last prayer with her sister. As Bluebeard attacks her, her sister and brothers kill the killer. The Castle and riches now belong to her. With her new wealth, she helps her siblings to marry well.

Blue Beard Illustration by Walter Crane

Blue Beard Illustration by Walter Crane

In Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, there are only 3 previous wives. Bluebeard takes Judith on a tour of the Castle. She asks for keys to each locked chamber. He tries to convince her not to examine all the rooms. She sticks to her position. The rooms contain things that show Judith more about her husband. This work considers colors like Prometheus does. There is a room with torture tools, the light goes red; another room has armaments, the light is yellow; a room full of jewels has golden light; a garden is blue-green; the fifth room shows Bluebeard’s properties in bright white light; the sixth is a lake of tears in shadow. Lighting is by Luke Kritzeck. Duke Blue Beard gave Judith chances to leave, but she insisted. She had the deadly virtue of sticking with her plan. Determination is her downfall. A lake of tears? Run, Judith, run! She wants the key to the seventh chamber. The room is barely lit, but she sees three wives: the love of his dawns, his love of noons, the love of evenings. Judith will be his love of night. She will become mute and isolated. He leaves and locks the door.

Photos by Brandon Patoc, courtesy of the SF Symphony

Yuja

Yuja