September 18, Davies Symphony Hall – It was a night for great, new music. Each of the selections were new in their own way. Composer Carlos Simon’s piece The Block (2018) opened the program with tremendous energy. Simon’s inspiration was the series of six paintings by Romare Bearden (1911 – 1988). These paintings are in the Metropolitan Museum, NYC. I have seen these paintings. They present the variety of shops, church, nightclub all on the same block in Harlem. The sites in the paintings have unique atmosphere, architecture, sizes, shapes, and especially human interaction and emotion brought out by the way humans express themselves and the buildings. The Block is six minutes long; those minutes include music that comes from the lives and stories that reach out to us from the street of this very specific, although also universal, street. It wowed us. Simon is Composer in Residence at the Kennedy Center, and the inaugural Boston Symphony Composer Chair among other honors. I think The Block will lead all of the audience to seek more of Carlos Simon’s work.

George Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F ( composed 1928) is often described as his best of his major works, Rhapsody in Blue, An American in Paris, Porgy and Bess, but it is not offered very often. I have heard bits of it, but never the whole Concerto and never in person. It was a Great Experience. Helene Grimaud is a fabulous soloist. Perhaps she was in touch with Gershwin himself, not imitating but surely she connected with every bit of her power and understanding — and even a bit of Grimaud is over the top masterful. The SF Symphony played brilliantly, and the guest conductor, James Gaffigan, made every note a thrill. It was an amazing performance. The first performance of the Concerto in F performed in San Francisco was January, 1937, the conductor was Pierre Monteux with Gershwin himself as the soloist. To grade Gershwin as a pianist, there is this quote from the conductor, Serge Koussevitzky, “As I watched him, I caught myself thinking, in a dream state, that this was a delusion, the enchantment of this extraordinary being was too great to be real.”

The San Francisco Symphony with James Gaffigan, Conductor, and Hélène Grimaud, Piano, in performance of Carlos Simon’s “The Block,” George Gershwin’s “Piano Concerto in F” and “An American in Paris,” and Duke Ellington’s “Harlem.” At Davies Symphony Hall on Thursday night, September 18, 2025. Photo: Stefan Cohen

The fantastic first movement of the Concerto begins with colors rising up with what was called a Charleston groove. The piano does not take time for its dreamy entrance until the snare drum introduces her. There is melody possessed by the symphony and the pianist. The pianist modifies the magic until it creates a blazing ending. The next movement was slow and bluesy. It has a pedestrian rhythm – pedestrian as in walking, not pedestrian as ordinary – and takes on a teasing, happy attitude. Through the Concerto I noticed tiny, blank moments, seeming like the white spaces of a Japanese print. The white spaces – very, very brief – are part of the rhythms. The concertmaster, Alexander Barantschik, sails into a playful, yet gentle solo. Gershwin describes the closing movement. “The final movement reverts to the style of the first. It is an orgy of rhythms, starting violently and keeping to the same pace throughout.” The movement allows the orchestra to trick the listeners with a fake exit, but it comes back with a mind-opening meeting of the world’s non-stoppable rhythms. Helene Grimaud gave the audience an encore: Brahms’ Intermezzo in Bflat minor, Op117, #2. It was gorgeous. If possible, the audience would still be applauding now.

An American in Paris, composed in 1928, has a joyful narration hidden in the various groups of instruments ranging from alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, percussion including small tom-tom, large tom-tom, wood block, xylophone, and taxi horns. Gershwin produced the rhythms of Paris as well as the sounds of Paris. The rhythms of walking, touring, maybe even gawking, keep “the American” absorbing and wondering at the City. Gershwin created his melodic theme on top of other themes. Some sound like the American has explored another neighborhood or he has slowed down because he found romance. Jazz informs the entire piece, especially the blues. This is the time for all the section leaders to play solos and then to pass along the story to the next instrument’s solo, like the trombone passes its melody to strings. Gershwin’s works are invigorated by the moods and rhythms of the varying musical sources. He keeps his life in classical way along with jazz and blues and sometimes the pop songs from Tin Pan Alley, his pop songs. The mixture becomes something else; it is Gershwin’s grasp that music is music.

The San Francisco Symphony with James Gaffigan, Conductor, and Hélène Grimaud, Piano, in performance of Carlos Simon’s “The Block,” George Gershwin’s “Piano Concerto in F” and “An American in Paris,” and Duke Ellington’s “Harlem.” At Davies Symphony Hall on Thursday night, September 18, 2025. Photo: Stefan Cohen

Duke Ellington’s piece, Harlem (1950), is a central piece of his sound and his vision. His personal elegance and his big band success made him and his music one of the greatest American composers. He passed away, in 1974, too young, but his image lingers as an iconic, American artist. (Although in his lifetime, that “iconic” was not in use.) Arturo Toscanini commissioned the piece for the NBC Symphony. However, it was premiered at an NAACP benefit at the 39th Street Metropolitan Opera House. Ellington described it this way, “a concerto grosso for jazz band and symphony orchestra.” The Duke published the list of places and events of Harlem that appear in Harlem. The list of 20 things include: “1. Pronouncing the word “Harlem,” itemizing its many facets – from downtown to uptown, true and false; 2. 110th Street, heading north through the Spanish neighborhood; 4. Upbeat parade; 5. Jazz spoken in a thousand languages; 7. Girls out of step, but kicking like crazy; 10. Church – we’re even represented in Congress by our man of the church; 11. The sermon; 12. Funeral; 13. Counterpoint of tears. The music encounters the many tunes and types of jazz that Ellington celebrates. There is the saxophone solo that takes pizzicato strings out for a quiet walk, a rhumba that identifies the Spanish neighborhood, bebop calls out crazy particulars from all the sections. Most of all it swings, calmly and tear-it-down swings. He is the band leader and truly great composer who taught several generations that “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing).” While jazz evolved through different ways to play, Duke Ellington got it all and gave us all of it.

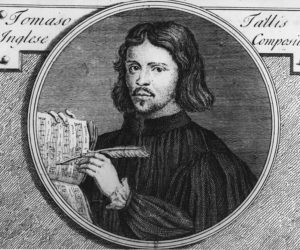

Magnus Lind

Magnus Lind Alban

Alban

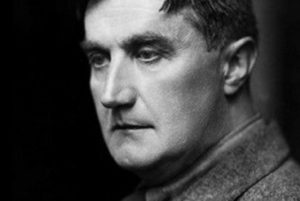

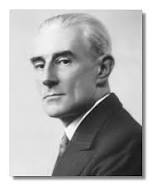

Ralph Vaughn Williams, composer (1872 – 1858), England

Ralph Vaughn Williams, composer (1872 – 1858), England

Anna Thorval

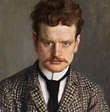

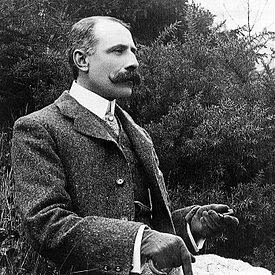

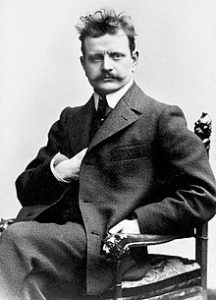

Anna Thorval Jean Sibelius, composer (1865 – 1957), Finland

Jean Sibelius, composer (1865 – 1957), Finland

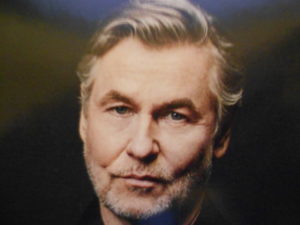

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony

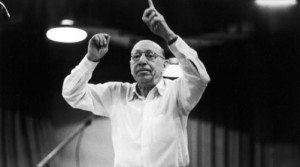

Einojuhani Rautavaara, compo

Einojuhani Rautavaara, compo Gemma New, Principal Conductor of the New Zealand

Gemma New, Principal Conductor of the New Zealand

Pablo Ferrandez, ‘cellist

Pablo Ferrandez, ‘cellist

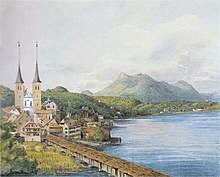

Felix Mendelssohn, 1809-1847, composer and accomplished painter, linguist, poet. This is a watercolor of Lucerne by

Felix Mendelssohn, 1809-1847, composer and accomplished painter, linguist, poet. This is a watercolor of Lucerne by

Blue Beard Illustration by Walter Crane

Blue Beard Illustration by Walter Crane

Example of

Example of

Ludwig Van Beethoven, Composer (1770-1827)

Ludwig Van Beethoven, Composer (1770-1827) Es

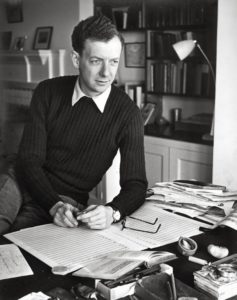

Es Benjamin Britten, composer (1913-1976)

Benjamin Britten, composer (1913-1976)

(L

(L

Joshua Bell

Joshua Bell