MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS conducts the San Francisco Symphony in Mahler’s 6th Symphony, March 30, 2023:

This giant and terrifying symphony was performed by the San Francisco Symphony with greatness as led by Michael Tilson Thomas.

Please note: Despite the fact that “terrifying” is the description, do not ever pass up an opportunity to hear it. It has a unique greatness and universal importance. It reaches each listener deeply, as though Mahler addresses us personally and the world at the same time.

Michael Tilson Thomas became Music Director of the SFS in 1995. He made San Francisco a Mahler town. Mahler’s name was painted on the Muni buses. MTT’s Mahler concerts were always sold out. In addition to his 12 Grammy Awards, he shared his musical knowledge and love. We all have grown through his gifts. The standing ovation that welcomed MTT as he entered the stage was given due to the respect and admiration the city continues to hold for him. He is now the Music Director Laureate of the San Francisco Symphony, conductor Laureate of the London Symphony, co-founder, artistic director laureate of the New World Symphony, and has conducted every major orchestra of the US and Europe.

Michael Tilson Thomas, Music Director Laureate, San Franciso Symphony

Michael Tilson Thomas, Music Director Laureate, San Franciso Symphony

We stood in respectful attention, applauding him to salute him and show our thanks, and then, he conducted music that terrified us all. I mean amazing, innovative, nightmare music composed exactly to warn us: something is coming. This music grabs the listener’s heart and comes this close to ripping it from the listener’s chest.

What is it all about? Mahler himself was stuck between thinking modern music would have an “underlying program,” and knowing that if stories, emotions, or experiences would be spelled out, the music will go flat as the listeners will not really be listening or baring their hearts to this very particular experience. So, he does not give up answers to the riddles.

From the first sounds of the first movement, Allegro Energico, Ma Non Troppo, we are in a threatening world. The music begins with quiet drums, the sound to accompany an army. When we first hear them they are far away, but the drums come nearer and louder. Soon, they are all around us. Trumpets and then oboes sweep in and over us. Suddenly, the music becomes more lyrical. The violins alternate with woodwinds. The music abruptly shifts to this swirling beauty, but it does not last. According to Michael Steinberg, the great writer of SFS’s program notes, the composer’s wife, Alma Mahler, believed this music is portraying her. I believe that she believed that, but, personally, I would not want to be the character in this passage. This music is on a precipice too high, too steep; the character – if in fact Mahler thought of a physical, living being identified in the music – the music character is going to be taken by surprise by another character carrying a big knife. That feels right. Mahler knew what was coming, I cannot believe Alma is there, but as the movement moves toward its end the marching returns. There is a powerful recapitulation. The Alma music returns. Is this a win for Alma? I do not think it will be. Some of this music changes direction roughly, quickly. I hear the changes to loveliness from threats and back again. Mahler is ironic. The sweepingly gentle sounds are not meant to stay. They are there to be eaten by predators. Human predators.

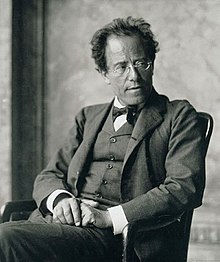

Gustav Mahler, born July 7.1860, Kaliste, Bohemia, died May 18, 1911, Vienna

Gustav Mahler, born July 7.1860, Kaliste, Bohemia, died May 18, 1911, Vienna

In rehearsals for the premiere, of his Symphony No. 6, Mahler was torn between having the Scherzo come before the Andante Moderato or vice versa. There were revisions after the first performance, but, in 1963, for the Critical Complete Edition, the editor, Erwin Ratz, settled on keeping the Scherzo second. It has stayed that way for most conductors. Mahler reversed the order of these movements in his second performance of No. 6 and in the second edition. Later, he regretted the change and Ratz believed that Mahler had wanted to go back to the first version.

The Scherzo has ragged rhythms. Nothing is metrically solid or predictable. It is extremely modern for its era in that way. Once again, Alma Mahler recorded her perception of the music. She thought that it represents “the arrhythmical play of little children.” Are the children of the music trying to run away? Are they imps, devilish but not cute- devilish? If they are playing – if there is in the music any vision of physical, solid personages – is that an image that Gustav Mahler would want us to see? The Scherzo’s sounds are broken up, wrenched around, even violent. If Mahler intended images of children, and I doubt it, they are either bad children kicking and beating on each other, or the music again has irony and sarcasm in it. If children are there, they are being lashed and brutally stomped.

After the harsh Scherzo, the Andante Moderato is melodic with gorgeous harmonies. There are sudden reminders of the hints of tranquility which were threatened by the marchers in the first movement. The cowbells played in the Allegro come back. The color and glimpses of love and loveliness waft about us. The Andante is a refuge from the violent Scherzo. Will we be allowed to stay in the refuge?

Absolutely not.

The Finale is longer than the first movement and longer than the two middle movements combined. The distant sound of cowbells in the Allegro, the first movement, is a reminder of a perfect place. It is far away, pastoral, peaceful. Nothing else, nowhere else is. The orchestra for this symphony is grand in numbers as well as in the music they create. There are many of each instrument. For example, there are 4 bassoons, plus a contrabassoon, 8 horns, 6 trumpets, 3 trombones plus a bass trombone. There are 2 timpani players, and a vast variety of percussion: bass drum, chimes, cowbells, cymbals, glockenspiel, hammer, rute*, 2 snare drums, tam-tam, triangle, and xylophone. *A rute is a bundle of birch twigs/sticks used to brush against a bass drum.

The Finale begins with the sound that something dropped; it is a low C. Then, there are many different instruments playing strangely together but not simultaneously and not playing the same thing. This music pulls our mental rug out from under our feet. What is going on? Why do I hear the harp, the woodwinds, more strings making these strange sounds? It is as though they are playing from different worlds, making music that jerks and pulls at each sound. The violins go rogue on their own. The drummers have a vicious sound in their relentless march. What is called the “fate” chord appears in multiple variations. The audience feels the music and seems to be forced to watch and know in their hearts the disintegration of what we had thought was the order of life, of our universe, or, at least, the order in musical sounds.

The lead percussionist appears in the empty chorus above the stage. He is seated on the lowest row. He has in his hand a hammer. It is huge. He strikes with it, and we feel the enormous sound reverberate in our spines. The music returns with an increased energy expressing the soldiers’ march growing ever more insistent and intense. They are coming for us. The music grows more wild and emphatic and scary. The hammer strikes again. The music changes. It is funereal. It blows away, losing force, becoming very quiet, nearly silent. There is a final huge, explosive A minor chord. The music has fulfilled its promise; it began with this chord and has returned, and so have the drums.

The music was terrifying. Michael Steinberg uses the metaphor of a hero “in the full flood of confidence and exaltation a hammer-blow strikes him down.” That is one way to think of what is happening in the music; it echoes a reflection written by Mahler. For me, that hammer blow was not aimed at only one person. It is an emblem of destruction. The horror of Symphony No. 6 is fitting for our world today. Extinctions of so many species. Water and air pollution shorten humans life expectancy. Money from fossil fuel corporations pollute politics. Wars, famine, gigantic fires, hurricanes, floods. Gustav Mahler died in 1911, three years from the start of World War I. What would have happened to him if he had lived deeper into the 20th century? Michael Steinberg, a child born in Germany, 1926, was saved by the Kindertransport to England, in 1939. Later, he moved to the US. Michael Steinberg reports in his program notes that Mahler believed the artist could “intuit, even to experience, events before they occur, that in fact he cannot escape the pain of such foreknowledge.” Mahler had experienced personal tragedy in 1907: his daughter Maria died, he discovered he had a serious, not curable heart ailment, and his directorship of the Vienna Opera ended in bad circumstances. However, perhaps through dreadful, personal knowledge and experience, he gave the world a warning of world-destroying tragedy.