San Francisco Symphony’s Music Director, Michael Tilson Thomas, led the SF Symphony in a dramatic, exultant performance of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, November 24, 2018. The program opened with Seven Early Songs by Alban Berg. Overall, the experience left the audience on its feet cheering and seemingly not sure what to do next. Leaving appeared to be out of the question. Soaring above the chairs was much more likely.

San Francisco Symphony’s Music Director, Michael Tilson Thomas, led the SF Symphony in a dramatic, exultant performance of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, November 24, 2018. The program opened with Seven Early Songs by Alban Berg. Overall, the experience left the audience on its feet cheering and seemingly not sure what to do next. Leaving appeared to be out of the question. Soaring above the chairs was much more likely.

Alban Berg Berg’s Seven Early Songs were written between 1905 and 1908 to be sung with piano. The orchestral score was not published until 1969. The songs are lovely, lyrical pieces set to the poems of seven poets. There are glimmering moments reflecting the natural world and Romantic reveries. The music has delicacy even as the songs express personal longing. Although the composer’s name can make some listeners apprehensive, in these songs Berg was not in his dissonant realm.

Alban Berg Berg’s Seven Early Songs were written between 1905 and 1908 to be sung with piano. The orchestral score was not published until 1969. The songs are lovely, lyrical pieces set to the poems of seven poets. There are glimmering moments reflecting the natural world and Romantic reveries. The music has delicacy even as the songs express personal longing. Although the composer’s name can make some listeners apprehensive, in these songs Berg was not in his dissonant realm.

The soloist, soprano Susanna Phillips has a clear, charming voice which was the perfect match for the music and the poetry. Good news: the performances of Berg’s Seven Early Songs were recorded for SFS Media.

The soloist, soprano Susanna Phillips has a clear, charming voice which was the perfect match for the music and the poetry. Good news: the performances of Berg’s Seven Early Songs were recorded for SFS Media.

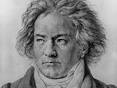

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (written 1822-1824) is great, enormous, gorgeous, heart-rending, uplifting. It is a grand, musical summation of what’s good about Western Civilization. It celebrates the values of brotherhood, unity among differences, equality, freedom, joy in life. It lifts the top of one’s head off and cheers the heart. The SFS performance was splendid, capturing the mystery as well as the expansive energy of life. Performing with the SFS were the SF Symphony Chorus and four soloist singers. These do not join in until the Finale. All were excellent: soprano Susanna Phillips (pictured above),

(L to R): mezzo soprano Kelley O’Connor, tenor Nicholas Phan, bass baritone Davone Tine.

(L to R): mezzo soprano Kelley O’Connor, tenor Nicholas Phan, bass baritone Davone Tine.

The giant, first movement is mysterious, disruptive, anxiety provoking. There is struggle and fear, but there is also a persistent forward motion that pushes the soul of the music onward. The Adagio has a loving expression; it is a tide pulling us–sometimes unwilling, sometimes just tired–by our hope and care. And then, the Finale. The Ode to Joy sings out as though our hearts will burst with hope for our highest selves to prevail through love and simple but ecstatic joy in friendship and living. At the end, the music speeds up, scampers, runs and jumps like an endless number of clowns happily tumbling out of a tiny car. I think that might be us: salamanders, penguins, humans; the jumble of life being alive.

The hopes that are vaunted in the Ninth are the same ones dashed when Napoleon crowned himself Emperor. Beethoven removed the dedication to Napoleon from his Third Symphony, the Eroica (written 1803-1804). It is a tribute to Beethoven’s dedication to these values that, now deaf, he still celebrated them with music from his heart and every fiber of his being. If he could keep his vision alive in terrible times, can his audience hesitate?

The performances of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and the performances of Michael Tilson Thomas’ From the Diary of Anne Frank the week before were programming to honor the 70th anniversary of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights.