February 6, 2025 – Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco – The San Francisco Symphony took giant steps into the music of Dmitri Shostakovich and Gustav Mahler. All efforts were successful and rewarded; the audience held its breath, stood to show appreciation, could not have been more excited by the music. The master composers of the 20th century sometimes shocked the music world with their new approaches to classical music: dissonance, layering of sounds, all with incredible virtuosity. Paavo Jarvi, conductor, led the SF Symphony through fresh, interpretive ideas for the playing of Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in F major, Opus 102 (1957) and Mahler’s Symphony No. 7 in E minor (1905).

Paavo Jarvi, conductor, winner Grammy Award for recording of Sibelius’ cantatas with the Estonian National Symphony, Grammaphone and Diapason Artist of the Year, Commandeur de L’Ordre des Arts et Lettres awarded by French Ministry of Culture.

Paavo Jarvi, conductor, winner Grammy Award for recording of Sibelius’ cantatas with the Estonian National Symphony, Grammaphone and Diapason Artist of the Year, Commandeur de L’Ordre des Arts et Lettres awarded by French Ministry of Culture.

Dmitri Shostakovich, composer (1906-1975)

Dmitri Shostakovich, composer (1906-1975)

Shostakovich wrote the Piano Concerto No. 2 in F major, Opus 102 for his son. Maxim wanted to appear as a soloist in order to help him enter the Moscow Conservatory. He had studied piano and conducting. Maxim asked his father repeatedly to write something for him to perform. Shostakovich at last produced this Concerto. Maxim’s solo was a success; he was admitted to the Conservatory. The Concerto was neither abandoned nor left only for youthful pianists. The father adopted this Concerto into his own concerto repertory and played it himself.

The piano soloist has the opportunity to show every possible piano technique one could have learned or which Shostakovich seems to have invented. Here is just one as described by James M. Keller, Program Annotator of SFS: “holding long notes and tracing melodies with separate fingers of a single hand.” I was there and heard it, but I cannot envision it. The composer has more up his sleeves: abrupt changes of meter, one from 2/4 to an unbalanced 7/8 and then breaking it down to multiple meters. The first and third movements were Allegro with the third much faster. The second movement, Andante, was a look back to the Romanticism of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff. Its beauties made the quick, quirky, challenges to the pianist all the more exciting and dramatic.

Kirill Gerstein was the soloist. He was fascinating to watch and hear. Very fast, great coordination of arms, hands, and individual fingers. A fabulous performance. Gerstein’s world premiere recording of Thomas Ades’ Piano Concerto with theBoston Philharmonic received the 2020 Gramophone Award. Kirill Gerstein, pianist; he performed Rachmaninoff’s Melodie, Op. 3, No. 3 as an encore on February 6. The audience was thrilled by the performance.

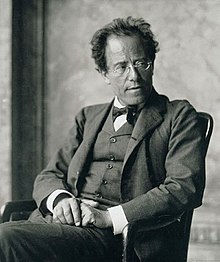

Gustav Mahler, composer (1860 – 1911)

Gustav Mahler, composer (1860 – 1911)

Mahler. Each of his symphonies is a whole world of actions, thoughts, cow bells, rustic dancers, military marches, desperate reaches for truth. Mahler said that he had started Symphony No. 7 from its middle, and that the whole would be symmetrical. Movements are balanced; there are two Nachtmusik movements. The The first movement is an Allegro moderato-Molto moderato (Andante). Nachtmusiks are in between the Slow-Allegro that opens the Symphony and the Scherzo: Schattenhaft (Like a shadow). We hear a very beautiful theme. The violin plays with elan. There are marches. A march becomes something else, something hidden until a wonderful lyric breaks through. The music is heard as a night time march. Cowbells break in surrounded by a sort of jump off a cliff in the strings section; the tam-tam and cymbals come in until the ‘cello sings alone. The Scherzo is ghostly. Drums and strings quarrel about their places. The Scherzo gives up as though its fabric frayed. The second Nachtmusik presents heartbeats and passion, a love song at night. Strangely, the guitar and mandolin make music that carries beyond the orchestral sounds. They are sad and lonely.The Finale charges with drums and slight references to Beethoven and Brahms. The Beethoven influence in Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 is not a quotation but a visiting cousin. Wagner’s Die Meistersinger seems to drift through, again not a quote just a suggestion of – this is a surprise – Wagner’s humor. It seems to me that the idea of Wagner’s humor is hilarious on its own. The symphony is triumphant. We are in nature and a part of nature. Drums return to remind us of the daylight, the thumping dancers, the gorgeous theme from earlier movements. Mahler will not let us down. He has so many ideas of the theme that he can offer them in layers or rearranging them or finding new sounds within them. He lets go of control; the sun shines. We are here.

Kirill Gerstein, pianist

Kirill Gerstein, pianist