The All Sibelius performance, March 14, was certainly one of the greatest concert programs I have ever heard. Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony, presented a program of Finlandia, Opus 26 (1899); Violin Concerto in D minor, Opus 47 (1905), with violinist Lisa Batiashvili; and Symphony No.1 in E minor, Opus 39 (1899). Each piece offered unique musicality. In the Violin Concerto, it seemed that Sibelius had discovered new notes which made sounds we had not heard before.

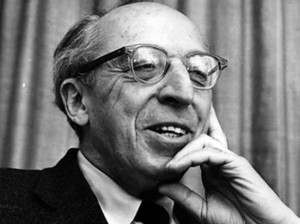

Jean Sibelius, Composer (1865 – 1857), Finland

Jean Sibelius, Composer (1865 – 1857), Finland

Finlandia may be the most familiar of all national anthems (with some apologies to France’s La Marseillaise*) Finnish history was about continual resistance while unable to fend off Sweden’s dominance since the 12thc. or the relentless interference of Russia. In 1894, Nicholas II became the Tsar. He demanded the February Manifesto that curtailed civil rights. In 1899, the Russians closed newspapers. An innovative way of announcing Finnish identity developed. A public show demonstrated Finnish history through tableaux and accompanying music and spoken narration. The tableaux started with beginnings of Finland, moved through the 17thc. in the Thirty Years War, and a short Russian hegemony in the 18th c. The ending was “Finland Awakes!” The program was supposed to gather charity for suppressed journalists, but the proclamation of Finnish nationalism was obvious. Sibelius and others were asked to contribute music. At first, Sibelius seemed not to recognize what he had made. Once he knew its strength, he rewrote it. In its first years, it was banned. Other countries gave it different names. In the Baltic countries, also dominated by Russia, it was just called Impromptu. It is a magnificent announcement of freedom and Finnish identity. While it is great music to hear, its power calls out to the listener whether Finnish or not. Seeing Esa-Pekka Salonen conduct it was thrilling. Sibelius answered his own question: “Why does this tone poem catch on with the public?…The themes on which it is built came to me directly. Pure inspiration.”

Violinist Lisa Batiashvili, soloist in Sibelius’ Violin Concerto in D minor, Opus 47, with the San Francisco Symphony.

Violinist Lisa Batiashvili, soloist in Sibelius’ Violin Concerto in D minor, Opus 47, with the San Francisco Symphony.

Music scholars and commentators will state that Sibelius composes with “profundity.” I experience the music as a profound look at life and the language of music. However, I cannot decide what Sibelius discovers and measures and understands in the music he creates. I have had teachers who liked to say that if that picture could be written, the artist would have written it instead of making it a painting. I think that is true except that most of us are only able to tell what we want to express in one art. For me, this Violin Concerto possesses mysteries of life and of music. Sibelius gradually reveals its musical truths. In the first movement, Allegro moderato, he provides a cadenza that is in the middle of the movement as a significant part of the concerto. The Adagio di molti, second movement, expands itself across a lake and seems to fly over a forest, but slowly. It is a vast presence which is the mystery. It does not pretend to communicate the mystery. One can only live it. The final movement, Allegro ma non tanto, has an emphatic but not overly quick dance stomping and turning. The rough dance movement creates the rhythm. The thing that is profound is easy to know. If we stop looking under every rock or examining every person, pine tree, or squirrel, it comes to us. Maestro Salonen brought out the delicate yet enveloping truth of this great concerto. He knows about Sibelius. Ms Batiashvili lifted the whole audience into the music’s life. The SFS played with profundity. This was a brilliant performance.

Sibelius’ Symphony No.1 in E Minor, Opus 39 was the second half of the concert. The audience was on its feet cheering Sibelius, Salonen, and the SF Symphony. The program notes by James M. Keller describe how close Helsinki is to St. Petersburg both geographically and musically. Sibelius surely was familiar with Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6. Keller also points toward influences from Berlioz. As I read the information after hearing the Symphony, I thought that Sibelius may have admired their works but at most they were a jumping off point. I was relieved to read that Keller ended by acknowledging Sibelius’ “distinct language.” This symphony is uniquely Sibelius. As led by Esa-Pekka Salonen, who called Sibelius perhaps the greatest Finn, I felt I was hearing the music as Sibelius would want it to sound. The music begins with Andante, ma non troppo-Allegro energico. There is a long, winding solo clarinet which attracts the timpani to play under the imaginative circles of the clarinet’s sound. This movement introduces the main themes and motifs of the symphony. That is what happens, but, of course, the audience does not hear the 4th movement rediscover these themes simultaneously with the 1st movement. Writers writing about music they have heard many times forget that the music can be new or seldom heard to the audience. It is a lucky surprise to charm us, turn the clarinet and timpani into the instruments of a snake charmer. We are hooked into this particular world of sound, all new.

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director of the SF Sympony, conducts the All Sibelius program, March q4, 2024

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director of the SF Sympony, conducts the All Sibelius program, March q4, 2024

The 2nd movement, Andante (ma non troppo lento) does begin quietly and slowly but not too slowly, as the description advises. There are moments that sound tragic; then, it expands into a large and angry message. There are references to recall the original themes, and this time it ends calmly. The 3rd movement, calls itself Scherzo: Allegro, but there is not a note implying a joke or lighthearted moment. It sounds more like a struggle; there are questions that cannot be answered. It ends without finishing the violent questions and suddenly, it stops. It leads to a wail of protest in the 4th movement. The strings bring in the 4th movement, Finale (Quasi una Fantasia): Andante-Allegro molto. The music is serious and deeply emotional. It returns to the themes introduced in the 1st movement, only this time they are fortissimo in strings with winds and bass accompanying as the form of a giant kite made of the individual parts of the orchestra and Maestro Salonen breaks free and flies. The audience was on its feet, staring ahead, looking like something completely surprising had happened to them, cheering Sibelius, Salonen, and the SF Symphony. An experience. A marvel.

The SF Symphony stands to applaud Maestro Salonen at the end of the Sibelius Symphony No. 1. Maestro Salonen bows to the musicians.

The SF Symphony stands to applaud Maestro Salonen at the end of the Sibelius Symphony No. 1. Maestro Salonen bows to the musicians.

Photos by Brandon Patoc courtesy of the San Francisco Symphony

Charles Wuorinen ( New York, 1938–)

Charles Wuorinen ( New York, 1938–)

Behzod Abduraimov ( Uzbekistan, 1990–)

Behzod Abduraimov ( Uzbekistan, 1990–)