May 18, 2023, Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco – The San Francisco Symphony performed the enormous and heartbreaking War Requiem, Opus 66 (1961) with soloists Jennifer Holloway, soprano; Ian Bostridge, tenor; Brian Mulligan, baritone; the San Francisco Symphony Chorus with Joshua Habermann, guest conductor; and the Ragazzi Boys Chorus with Kent Jue artistic and executive director conducting. The soloists, soprano, bass, and tenor performed with deep understanding of the texts and, in addition to the power of their voices, communicated the painful emotions of this work.

Britten assembled a multitude of artists in groups and individuals, not as one voice and not with one anthem. There were two different and sometimes opposing texts: the Catholic mass for the dead, Missa pro defunctis, and poetry by Wilfred Owen, one of England’s World War I poets. There are nine of Owen’s poems. In case you are not familiar with Wilfred Owen’s work, it is worthwhile to know that he fought in the war but was not enthusiastic for it. Before the war, Owen had considered entering the ministry. Beginning December, 1916, he was on active duty in France, then spent 5 months in a hospital, then was sent back to France. He received the Military Cross award. He fought in the trenches, saw hideous wounds and deaths among his comrades, and, while leading his company across the Sambre Canal, was killed by machine gun fire. His death was on November 4, one week before the Armistice.

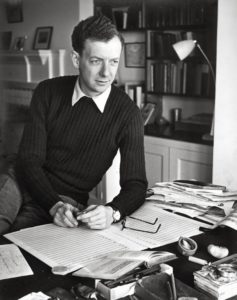

Benjamin Britten, composer (1913-1976)

Benjamin Britten, composer (1913-1976)

In Britten’s Requiem, the mixed chorus and the full orchestra perform texts from the Missa pro defunctis in Latin. The male soloists with a chamber sized group of the orchestra sing the Owen texts in English. The Ragazzi Chorus is not seen. It sings its parts of the Missa from behind the wall enclosing the chorus loft. Their sound is quiet and sounds as though coming from a great distance.

Britten uses all traditional parts of the Missa: Requiem aeternam, Dies irae, Offertorium, Sanctus, Agnus Dei, then closing with Libera me. In this music, these sections become an opera of belief and also condemnation. The solo soprano is in the chorus loft with the Symphony Chorus, but they are behind her on their higher rows. She sits alone in the front and lowest row. She appears like a figurehead on a ship or the ancient Oracle, even though she declaims Christian faith and imperatives. Her first majestic singing is in the Dies irae. The chorus does not adopt her outlook. Instead, they sound weak and doubtful. Then, in an example of the opposition of the Latin text and Owen’s poems, the tenor and baritone sing from the deeply ironic poem, “The Next War.”

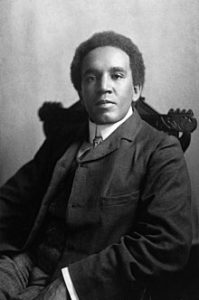

Wilfred Owen, soldier, poet (1893-1918)

Wilfred Owen, soldier, poet (1893-1918)

If one had merely listened to the unique orchestration and the use of bells and many versions of percussion including tambourine, triangle, castanets, Chinese blocks, snare drums, bass and tenor drum, that listener may have awakened to Owen’s poem, The Parable of the Old Man and the Young. It is sung by the tenor and bass with the chamber orchestra. It is Wilfred Owen’s answer to the story of Abraham taking Isaac to a place of sacrifice. Abraham begins to follow G-d’s request to sacrifice Isaac, but then an angel, sent by G-d, stops him, saving Abraham from the murder of his son and saving Isaac’s life.

In the Owen poem, Abraham kills his son. The music is harsh, discordant, and, despite the horror of the death, it is worse because it is roughly torn from the story most listeners will know. As that breath taking, wrenching event is told, the boys of the Ragazzi can be heard singing softly, far away.

“When lo! An angel called him out of heaven,/Saying, lay not thy hand upon the lad,/Neither do anything to him. Behold,/A ram, caught in a thicket by its horns;/Offer the Ram of Pride instead of him./But the old man would not so, but slew his son, -And half the seed of Europe, one by one.”

Rather than the war to end all wars, this was a war that killed a generation of men.

The Sanctus opens with the soprano magnificently singing while the chorus chants. It has become a song of praise. The last movement, Libera me (Deliver me) the Baritone sings“I am the enemy you killed, my friend/I knew you in this dark; for so you frowned/Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed./ I parried, but my hands were loath and cold.”

Together the tenor and baritone sing: “Let us sleep now…” as though they have learned from engaging in the battle with each other, as though they could go forward peacefully. They cannot do it; they are dead.

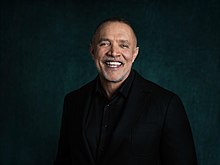

(L to R) Jennifer Holloway, soprano; Ian Bostridge, tenor; Brian Mulligan, baritone

(L to R) Jennifer Holloway, soprano; Ian Bostridge, tenor; Brian Mulligan, baritone

The War Requiem ends with the boys’ chorus, mixed chorus, and soprano singing “May angels lead you into Paradise,/may the martyrs receive you” and “Grant them eternal rest, O Lord,/and let everlasting light shine upon them./May they rest in peace. Amen.”

The prayer sounds peaceful. Their rest could be tranquil. I do not think we have traveled through the War Requiem in order to believe the dead, piled up like giant haystacks, are all better now.

Benjamin Britten was a pacifist. Wilfred Owen, after having considered a life devoted to a church, found that he could not trust the institution of churches. He could find no Christ in the churches because killing was not only allowed, but supported. The Agnus Dei/Lamb of G-d section of the Missa, repeats “Lamb of G-d, who takes away the sins of the world,/grant us peace. “ But they sing “Grant us peace.” only once.

Ludwig Van Beethoven, Dec. 16,1770 –

Ludwig Van Beethoven, Dec. 16,1770 –  Samuel

Samuel  Mich

Mich Conductor Xian Zhang

Conductor Xian Zhang

Photograph courtesy of the website of artist/animator Gregoire Pont from the premiere of L’enfant et les Sortileges, Lyon, France, 2016.

Photograph courtesy of the website of artist/animator Gregoire Pont from the premiere of L’enfant et les Sortileges, Lyon, France, 2016. Fire in L’Enfant et les Sortileges

Fire in L’Enfant et les Sortileges

(L to R): mezzo soprano Kelley O’Connor, tenor Nicholas Phan, bass baritone Davone Tine.

(L to R): mezzo soprano Kelley O’Connor, tenor Nicholas Phan, bass baritone Davone Tine.

Stanislav Trofimov

Stanislav Trofimov

Tom Hulce enacted Mozart in Amadeus

Tom Hulce enacted Mozart in Amadeus F. Murray Abraham as Salieri in Amadeus

F. Murray Abraham as Salieri in Amadeus