Chamber music is loved by many and ignored by others. That reminds me of the text on cookie packages: sold by weight not bulk. In case you do not frequent the cookie aisle, that means that if the cookies inside do not seem to fill the bag to the top, that does not mean you are getting fewer cookies! Chamber music has heft and impact. The concert on Sunday, December 18, is a good example. Stars of the San Francisco Symphony gathered to play Pastorales de Noel, by Andre Jolivet; Phantasy Quartet in F minor, Opus 2, by Benjamin Britten; and String Quartet no. 2 in B-flat major, Opus 87 by Felix Mendelssohn. it was an interesting program with seldom heard music which offered innovative composing.

Andre Jolivet, French composer, 1905-1974

Andre Jolivet, French composer, 1905-1974

Jolivet was part of a group of young French composers, La Jeune France, which included Olivier Messiaen. Their aim was to develop spirituality in music. Jolivet admired Schoenberg and Varese, but his own work evolved in other ways. He was the Music Director of the Comedie Francaise, an anchor of the French dramatic arts. He created “incidental music” for classic theater by Shakespeare, Moliere, and Greek dramas. Pastorales de Noel, composed in 1943, the opening piece on this concert, was something completely different from any expectations of “normal” chamber music. First, the combination of instruments was surprising: bassoon, flute, and harp. Each of the four pieces making the whole had a title referring to the Christmas narrative. There was “The Star,” “The Magi,” “The Virgin and Child,” and “The Entrance and Dance of the Shepherds.” Knowing the names of the images, one could imagine the star lighting the sky. The music for the Magi sustains a rhythmic processional; the creche scene is hushed and peaceful. The shepherds bring energy and a folk dance feeling which is exuberant but controlled. It is a lovely, inventive piece with its complexity well hidden behind the communication of Christmas images. The fine, sensitive performers were Catherine Payne, flute; Meredith Clark, harp; Steven Dibner, bassoon.

Steven Dibner, Associate Principal Bassoon in the SF Symphony, introduced the program by explaining that many years ago, he convinced the SFS that they needed a Chamber Music series. In addition to offering the wonderful, extensive chamber music repertory, it also gives the audience a chance to get to know the players and see them better making music. He is right. It is a much more personal experience to see a small group of musicians taking over Davies Hall.

Steven Dibner, Associate Principal Bassoon in the SF Symphony, introduced the program by explaining that many years ago, he convinced the SFS that they needed a Chamber Music series. In addition to offering the wonderful, extensive chamber music repertory, it also gives the audience a chance to get to know the players and see them better making music. He is right. It is a much more personal experience to see a small group of musicians taking over Davies Hall.

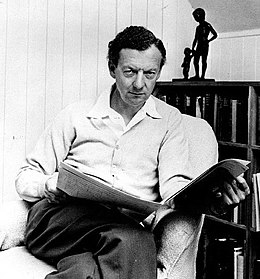

Benjamin Britten, composer, 1913-1976

Benjamin Britten, composer, 1913-1976

English composer, Benjamin Britten, was beginning the process of becoming well known when he wrote Phantasy Quartet in F minor, Opus 2, 1932. He had written a Phantasy Quintet For Strings, in 1932. His interest in “phantasy” compositions led him to create another one, this time three strings with an oboe. While it has 4 episodes which could be considered movements, there is a unity in the four that makes the sound flow like a ribbon. The music begins with unusual sounds coming from the cello with no particular rhythm. Then, the violin, viola, and oboe join the fantasy. The movements are Andante alla marcia ( like a march) —, Allegro gusto (with gusto)—, Con fuoco (with fire)—, Tempo 1: Andante alla marcia. Ending where the music began completes the sense of one fascinating, stream of music. It is something different that captures the listeners’ intellect as well as emotional and aesthetic pleasure. The future of Britten’s work and English music is beginning here. The musicians were James Button, oboe; Jessie Fellows, violin; Katie Kadarauch, viola; Amos Yang, cello. They delivered with aplomb the engaging Britten music with its newness.

Felix Mendelssohn, composer, 1809-1847

Felix Mendelssohn, composer, 1809-1847

Mendelssohn’s String Quintet No. 2 in B-flat major, Opus 87, filled the second half of the program. This work energized the concert. The music opens as a dashing, romantic hero on horseback. Thrilling but never reckless; the Quintet explores its world, just as the composer explored his. These travels resulted in his Scottish Symphony and Italian Symphony. He made ten trips to Britain. He played for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Both royals played his music and thought of him as a friend. This Quintet includes two violins, two violas, and a cello. The opening movement, Allegro vivace, is so sprightly and energetic that Allegro alone is not enough. It needs the vivace to impress the musicians how lively it must be, and it was. There is a burst of inspiring energy from the first breath. The Andante scherzando, second movement, is an inventive approach. Andante means a walking rhythm, not running or jumping. A scherzo, a joke, could be played as something droll or satirical or even bitter. The performers found the depth in their interpretation. This drew the listeners into a musical mystery which would not let them go. The new direction for the Quintet is extended in the third movement Adagio e lento. The lento, meaning slowly, intensifies the slow adagio movement. Something is happening in this music; there is a change from the spirited beginning to these middle movements. Mendelssohn does not create music without a deeper philosophy. One feels the way through the cave of life, trying to find meaning in the darkness. A great artist, he knows dark and light and the need to express this truth. He does not despair or leave us there. He ends with a brief, cheering lilt, all the more meaningful because he has shown us the dark. The extraordinary performers included Jessie Fellows, violin; Nadya Tichman, violin; Katie Kadarauch, viola; Katarzyna Bryla-Weiss viola; Sebastien Gingras, cello.

A PERSONAL NOTE REGARDING MENDLESSOHN: When I was a very young piano student at the St. Louis Institute of Music, the teachers would give students a small bust of a composer if they played well or completed a section of learning. Did any of you collect those same little statues? I remember the teacher rattling off a list of the greatest composers. I think I asked her, though she may have volunteered the information, why Mendelssohn was not included? She explained to me that Mendelssohn was only a copyist. His music was not original and never could be because of his origins. Did she flatly say it was because he was Jewish that he could never create great music and only could be a parasite on the other, real composers? I do not remember that, but I soon learned that that was the way he was seen: Jewish and not very good. His statue in Leipzig was erected in 1892 in recognition of his efforts that made Leipzig recognized as a city of music. It was torn down in 1936. A city official who hated Jews and liked Nazis got together Nazi sympathizers to tear it down and hide or destroy it. The Mayor of the city, Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, was out of town. When he returned, he tried to have it replaced, but it was never found. On October 18, 2008, Kurt Masur, the great conductor who had led the Gewandhaus orchestra for 25 years, spoke at the unveiling of the new Mendelssohn monument, a replica of the original. The Gewandhaus had been destroyed by bombs, 1943-44. Its rebuilding began in 1977 with Masur laying the foundation stone. Masur noted that on one side was the Gewandhaus, an institute made prominent by Mendlessohn, and on the other side the Thomaskirche where JS Bach spent most of his career. Mendelssohn was responsible for the “rediscovery” of Bach, especially accomplished by his performance of Saint Matthew’s Passion. Mayor Goerdeler had given the London Philharmonic permission to lay a wreath at the Mendelssohn statue. Now, the replica has this note written on stone: “May the language of music speak only of noble things.”

Leslie Friedman