The San Francisco Opera’s presentation of Billy Budd ended with the matinee, Sunday, September 22, and still the music and drama play in my mind. The voices: absolutely first rate. The acting, set, costuming, direction, orchestra and conductor: all superb. The San Francisco Opera Orchestra, led by Lawrence Renes, captured Britten’s oceanic sound as well as the delicacy of the piccolo solo as Billy waits for execution. Readers, you may have missed this production of Billy Budd, but I hope this report encourages you to attend the opera when and where you have the opportunity. The excellence of this production promises greatness in the rest of SFO’s season.

Benjamin Britten, major 20th century English composer, wrote the music set to a libretto by the great English author, E. M. Forster(Passage to India, Room with a View, Howard’s End) and Eric Crozier, a librettist and theater producer who directed Peter Grimes, Britten’s first opera, 1945, at Sadler’s Wells theater, in London. He also wrote the libretto for Albert Herring, another Britten opera. Billy Budd is based on an unfinished novella by Herman Melville. His manuscript was discovered one hundred years ago; this year is the two hundredth anniversary of Melville’s birth, in 1819. Now considered one of the central, most significant American authors, even Melville’s Moby Dick, disappeared soon after publication. He had critical and financial success with his first two novels, Typee and Omoo, but, after his later works were ignored, gave up writing novels, tried poetry, and then, in 1888, began Billy Budd. Melville passed away, in 1891.

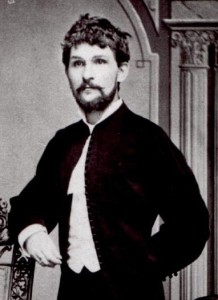

Benjamin Britten (Nov. 1913-Dec. 1976)

Benjamin Britten (Nov. 1913-Dec. 1976)

Both Britten and Melville had a close relation to the sea. Britten was born in Lowescroft, a fishing port on England’s east coast. Melville actually was a sailor on whaling ships and in the Navy. His travels took him around the world. He had first hand knowledge of the closed community on board ship and knew about the English tradition of “impressing” ordinary folks, kidnapping men and boys, to be in the Royal Navy. Britten’s music for Billy Budd captures the surging sound and rhythm of the ocean. The opera does not try to follow the novella exactly. Forster uses the characters, setting and part of the story line as a way to jump into some themes which Melville did not develop. These include the spiritual resolution offered in song by Billy and by Captain Vere. Melville did not appear to have a strong focus on religion or a specifically Christian understanding of death. Also, in the opera, there seems to be more awareness of what contemporary music writers refer to as “homo-erotic” sensuality. Having spent six months or more at a time on ships, Melville would know about relationships, but to the extent it appears in Billy Budd or Moby Dick it is more a reflection of reality than a theme.

American tenor William Burden portrayed Captain Vere with straightforward nobiity. His voice projected clarity, balance, humanity; it is a voice one could hear with pleasure for a long voyage.

American tenor William Burden portrayed Captain Vere with straightforward nobiity. His voice projected clarity, balance, humanity; it is a voice one could hear with pleasure for a long voyage.

The opera opens with Captain Vere, now old, beginning the story of what happened on his ship, HMS Indomitable, in 1797. In Michael Grandage’s brilliant production, the audience is enveloped in the ship. Built on the stage in a horseshoe shape opened toward the orchestra and house, the set shows the decks of the ship, the men/SF Opera Chorus kneeling on the deck/floor continually to scrape the salt off the ship. The production fit the opera ideally; I can only imagine it now with this set and direction. It also worked so well that the violence –flogging the Novice and hanging Billy –happened offstage as in classic Greek drama. The atmosphere is close; there is nowhere to go. There are no families, no pub, no market. The common sailor’s life is dictated by work enforced by cruelty. Three new sailors are brought aboard. They have been impressed and taken from the ship ironically named the Rights o’ Man. Claggart, the master-at-arms, uses the name of the ship as his first attack on the new sailor. Billy calls out farewell to friends and to the ship giving Claggart the opportunity to call Billy a revolutionary who must be watched.

From his first appearance on the Indomitable, Billy, has “handsomeness, beauty and goodness.” When he is under pressure, he stammers. He is liked and even admired by the men and hated by Claggart. The hatred has no special reason. It is total hate like Iago’s for Othello, a man who is better than he in so many ways. The audience feels apprehension that something terrible will happen and waits in suspense to know how it will unfold. Claggart preys on the weak Novice who was brutally flogged. He threatens the Novice with more violence if he does not cooperate in setting up Billy. At first, the Novice refuses because Billy is kind and good, but fear defeats him. This cast of seventy-five artists, forty-four of them from the SF Opera Chorus, is astoundingly good. Each projects a character, and all create a true crew. There are moments that lighten the tension. For example, in Act I, scene 3, the crew gathers to sing a late 18th century version of Rap, with each man’s rhyming verses entertaining the crowd. Billy offers to get Dansker tobacco. American bass-baritone, Philip Skinner, sings Dansker with a great, satisfying voice appropriate for a brave, true friend. Billy’s tobacco has been taken from his kit. He fights with Squeak who was set by Claggart to make trouble for Billy. American tenor, Matthew O’Neill as Squeak with presence and just the right voice creates the character willing to betray Billy who is then betrayed himself. The men are eager to attack the “Frenchies,” but fog and still winds keep them from a battle.

The crew of HMS Indomitable ready to attack the French.

The crew of HMS Indomitable ready to attack the French.

Claggart (Van Horn) presses his case with Vere (Burden).

Claggart (Van Horn) presses his case with Vere (Burden).

Then Claggart tells Vere that Billy is fomenting mutiny and has gold coins to bribe the crew. Given a chance to defend himself, Billy stammers. In frustration he strikes Claggart who falls dead. Vere calls three officers to serve as a court-martial. They can believe Billy, but Billy struck and killed an officer. By the Laws of War, he must die. The three officers are horrified by what they have done and ask Vere, the only witness, to stop the process, but Vere says he cannot.

Billy taken away for execution.

Billy taken away for execution.

Surely one of the most chilling, touching and beautiful songs in the opera is Billy’s solo while he waits to be executed. He is frightened and does not want to die. He imagines himself under the water, gone. Then, he imagines that he will be anchored by, what? Is it faith? Is it heaven? He sings, “I’m strong and I know it, and that’s enough.” He sings, “I’ve sighted a sail in the storm, the far–shining sail, and I’m content.” Vere reappears looking back through time and repeats Billy’s words about that sail. Vere also says he could have stopped it. And there’s the eye-opening, hair raising moment. He had said there was nothing he could do. He had to follow the letter of the law although he knew he was killing an angel. Now, he says, both that he could have done something and that he is “content.” In the battle between good and evil, Claggart won, but he only won by being killed. The optimism that the Goodness of the Good will find a safe harbor and that the humane regret of Captain Vere will somehow reach a contented resolution does not seem very Melville-like. The ambiguity of human life does, though. Imperfect and unfinished, just like the novella Billy Budd, that is what we are. Perhaps wisdom is to decide to be content. Perhaps.

Photo of John Chest by Andrey Stoycher; Billy taken for execution, Claggart with Vere, whole crew by Cory Weaver, courtesy the San Francisco Opera. Future operas of SFO’s season: The Marriage of Figaro, Oct. 11-Nov. 1, Manon Lescaut, Nov. 8-26, Hansel & Gretel, Nov. 15-Dec. 7.

John Chest, American baritone, portrayed Billy Budd. Eager, confident, honest, with a voice that possessed Billy’s “handsomeness, beauty, goodness” and pulled the listener into his heart while breaking the heart of the listener.

John Chest, American baritone, portrayed Billy Budd. Eager, confident, honest, with a voice that possessed Billy’s “handsomeness, beauty, goodness” and pulled the listener into his heart while breaking the heart of the listener.