Guru Shambhavi Dandekar presented DARPAN, in the Mission City Center for the Performing Arts, Santa Clara, CA. Oct. 20. Darpan, in English, means mirror. This is a wise title for the magnificent Kathak performances she choreographs and dances. It allows her students from beginners to professional to look at their progress in their art. It also shows the audience to themselves. Do they feel immersed in the dance and music? Do they lose themselves in the beauty of thought, movement, and music combined? Can they bring themselves closer to that place where one loses self-awareness? The same time their being is engulfed by time and space, time and space disappear. That is how the audience participates in the dance. It can happen if one is ready.

This year is the 10th anniversary of S.I.S.K. the arts center started by Guru Shambhavi: Shambhavi’s International School of Kathak. S.I.S.K. produces a Darpan ever two years. This year’s program was sensational. It was hard to believe but true; it was even on a higher level than the previous one. The program was varied, but all of the selections were performed perfectly. Guru Shambhavi choreographs dances which can be performed with the skills of the dancers. And, they rehearse! This made each dance and dancer successful and beautiful.

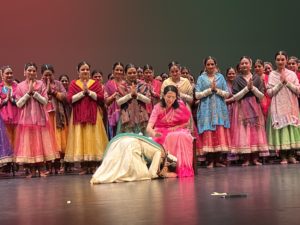

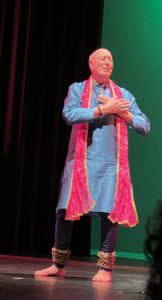

Guru Shambhavi Dandekar, in DARPAN concert, October 20, 2024.

Guru Shambhavi Dandekar, in DARPAN concert, October 20, 2024.

Mr. Vineet Mishra was the emcee. He gave brief introductions to each dance. That was very helpful to me as I do not always recognize names of masters of dance and music.

Dancers who had begun their study at the beginning of this year were excellent at their assignment. They danced to pure musical notes that form Indian classical music: SA, RA, GA, MA, PA, DHA, NI. Their dance celebrated melody through their rhythmic footwork, hand movements, and graceful body movement making a design in space. Their study included speed, precision, strength, and endurance. As I quoted that list I remembered a poster that said, “Dance is work.” The audience sees the result but not the effort.

The next level of dancers also shone in their dance, Trivat. The focus shifted from melody to rhythm and from music notes to syllables of the PAKHAWAJ, a drum of classical Indian music. It has a barrel shape, open sides, and thin, leather straps. It was a pure, technical dance; the dancers more than met their challenge. It was presented as an Ode to Nritta, pure dance movement and footwork. The dancers showed incredible footwork and fine stage presence.

Nritya Keli was a dance of nostalgia inspired by movements of childhood play. It was a charming dance that suggested happy, playful times. It took the audience away from the technological world to the fun and beauty of being outdoors with friends, a rope, and maybe a ball, too.

HORI is a dramatic and moving solo dance for Guru Shambhavi Dandekar. This was its premiere performance. A young woman has lost her sight. Her sweetheart comes on the day of Hori. He tells her that this year, the holiday will be special for them; they are alone together. Despite her disability, she has a strong spirit. He has brought her a plate covered with many colors. Gently, he describes the colors as he paints them onto her face.

They celebrate Holi, the festive holiday of colors and the spiritual treasure of playfulness. Hori is a genre of semi-classical singing, especially sung during Holi. The songs of Hori/Dhamar are related to Radha-Krishna Leela. Krishna’s Leelas are Divine Play. I read that Karma is for the self, but Leela benefits the whole world.

When it is the young woman’s turn to paint colors onto his face, she chooses the most powerful color, love. It means that love is not seen but felt in the heart.

Guru Shambhavi revealed her acting abilities in Hori. In fact, she did not seem to be acting at all. She lived in the character and became the other person: her challenges, spirit, and love. I still see her turning around to sit in a chair. She reaches out with her arm to give a gift. Her smile out shined the stage lights. I did not know the story, but suddenly knew my eyes were full of tears, and I felt happy.

In her DARPAN productions, Guru Shambhavi finds ways to present both the traditional dance movements and contemporary art. To open the second half of the program, she presented GURU, a music video. It pays homage to the Guru-Shishya Parampara, the ongoing flow of knowledge from the Guru to the student. The setting was a beach with the ocean just yards away

Guru Shambhavi salutes her Guru- her mother

Guru Shambhavi salutes her Guru- her mother

And honors Guru Maneesha ji with gifts and gratitude.

A woman, played by Guru Shambhavi, is practicing her arm movements. She cannot get it right. As she become more frustrated, she feels the movements get worse. She falls to the sand. Another woman, played by Guru Maneesha ji, Guru Shambhavi’s mother and guru, walks in the sand to encourage the dancer. The dancer works to get the movements precise; the Guru is helpful but strict. When the dancer is moving well, the Guru walks away. The dancer continues moving, sees another dancer having the same problems, and becomes the guru for that next dancer. This was a wonderful way to experience the Guru relationship. The director is Ashay Javdekar, also Unni and Priyanka.

S.I.S.K. has an innovative training program, Global Distance Learning for adult beginners. It began in 2021 and now has 200 students in 12 countries. Using a split screen on the back and live dancers performing on stage in their dance, Rhythm Scape, executed footwork, body movements, and formations in a surprising, delightful multi-dimension dance

Barkha, is a dance celebrating the monsoon; “the longing of the earth to unite with the sky. Peacocks “dance in bliss,” unfurling their feathers. It is set in a cycle of 12 beats. A beautiful concept and the dance fulfilled it.

Mrignayan is a dance to project the sweetness of romance, as demonstrated by Radha and Krishna. In this dance, Krishna is called Rasiya, and Radha is the protagonist. Mrignayani means “the doe eyed beauty,” referring to Radha. The accompanying composition is from the medieval saint Purushottamdas. The dance incorporates North Indian folk dance. All aspects of the dance honor the love of Radha and Krishana

The grand finale was Taalmala. It offers the essence of Indian music and means “a garland of Taal –s.” Taal is rhythm. The choreography is also an expression of higher math. The rhythms are cyclical and accent the first beat of each rhythm which is called SAM.

Taalmala is a waterfall of rhythms. It has great energy but never breaks away from the restraints of each beat pattern. There are 6 distinct Taal –s, and each has its own number of beats. Of course, it is not enough to tap or clap or nod the beats, the performers must keep dancing and making designs in space. I particularly admire Guru Shambhavi’s ability to have her dancers use all of the stage. It makes the dances alive in three – maybe four – dimensions. Watching this dance is exciting, especially if one tries to keep the counts! Here are the rhythms: Tritaal – 16 beats; Jhaptaal – 10 beats; Dhamaar – 14 beats; Chautaal – 12 beats; Roopak – 7 beats; Ashtamangal – 11 beats.

All dancers are on the stage, keeping their rhythms, working their feet and bodies, looking fabulous, and then, they make a V shaped form on the stage floor with their Guru Shambhavi standing at the up stage point of the V with her arms up in parallel. This program was a magnificent work of art. We must wait two years for the next Darpan. The line forms now.

All photos by Yamini Mitter.

All photos by Yamini Mitter.

Liv

Liv

Helene Grimaud

Helene Grimaud Gabriel Faur

Gabriel Faur

Areta Zhulla, Violinist, fi

Areta Zhulla, Violinist, fi

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, composer (1756 – 1791)*

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, composer (1756 – 1791)* Emanuel Ax, pianist

Emanuel Ax, pianist

E

E

Emanuel Ax, 2015

Emanuel Ax, 2015

Dr. Tria Blu Wakpa, Assist. Professor, UCLA’s Department of World Arts & Cultures/Dance

Dr. Tria Blu Wakpa, Assist. Professor, UCLA’s Department of World Arts & Cultures/Dance

Jasmine Jimison: Principal Dan

Jasmine Jimison: Principal Dan

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony.

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director, San Francisco Symphony.