Near the end of Amadeus, the award winning movie from 1984 which was presented by the San Francisco Symphony, April 6 & 7, with the SF Symphony present playing the film’s score and the SFS Chorus present performing the vocal music, there is a moment when a coffin is lifted out of a coach. As men walk forward carrying the coffin, the viewer noticed the coffin’s smaller end flap open and shut. Something was wrong with this picture. The coffin is tipped, a bundle covered in white cloth slides out; it lands on a pile of other bundles in a big ditch. That bundle was the body of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Mozart (1756-1791) painted by Johann Nepomuk della Croce

Mozart (1756-1791) painted by Johann Nepomuk della Croce

Dead at age 35, Mozart’s celestial music goes on.

This is a painful, gorgeous movie. Seeing it with live music accompaniment was a great benefit as hearing the music created in the moment made Mozart’s life’s work all the more real. The SFS Chorus had provided the vocal music in the film, another plus to the movie/live music experience. Conductor Constantine Kitsopoulos, the Symphony, Chorus, Choral Director Ragnar Bohlin all deserved the continuing cheers of the audience. “Wolfie,” as his wife Constanze calls him in the movie, wrote more than 600 works. That’s right, 600 works of perfect beauty; turn off the computer, now ( when you finish this short article is ok, too.)

Tom Hulce enacted Mozart in Amadeus

Tom Hulce enacted Mozart in Amadeus

Tom Hulce’s performance as the “loved by God” composer is breathtaking. He has the outrageous giggle, bawdiness, conscience-free, child-like behavior and the focused concentration of a true genius when at work. F. Murray Abraham as Antonio Salieri, the competitive, court composer devoured by jealousy, captures the many sides of a man capable of appreciating how extraordinary Mozart’s music is and still wanting to destroy him. Both actors were nominated for Best Actor Academy Awards; that time Salieri won.

F. Murray Abraham as Salieri in Amadeus

F. Murray Abraham as Salieri in Amadeus

The movie is so powerful that it is difficult to remind oneself that this is fiction based on some historical fact and a lot of historical rumor. No one can know what caused Mozart’s death. His grave was not marked; there is no hope for posthumous analysis. Renal failure is one interpretation, but more than one hundred explanations have been given. The rumor that Salieri poisoned Mozart was alive and well long after both composers were gone. In 1830, Alexander Pushkin, the great Russian author, wrote a play based on the rumor. The movie is based on the play by Peter Shaffer who drew on Pushkin’s work.

The movie plus live music phenomenon is made possible by a fancy computer rig. One could see the laptop on the Conductor’s podium. There was a pulsing, large, white dot and different lines which seemed to coordinate the entrances for music and chorus. Timing is everything. The live participants must not be even a nano-second early or late as the dialogue and some on-the-film music go on. It is a wonder. The 2018-2019 season offers films such as Jurassic Park and Mary Poppins with live music.

The problem with the rumor is that it is so believable. Artistic rivalry and deadly jealousy, not so surprising as one might wish. The audience experiences the suffering of a man who was, as the play’s Salieri sees, composing as though angels dictated to him. The loss of what more music he might have created is impossible to measure. Redwoods killed by drought, right whales going extinct, children made asthmatic by air pollution: all those losses of life and liveliness and the loss of Mozart himself. Humans got lucky that he was here at all. What if, after its few productions Don Giovanni had simply disappeared? We would all be less than we could be and not know it.

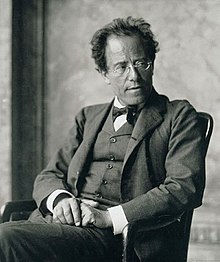

Charles Wuorinen ( New York, 1938–)

Charles Wuorinen ( New York, 1938–)

Behzod Abduraimov ( Uzbekistan, 1990–)

Behzod Abduraimov ( Uzbekistan, 1990–)

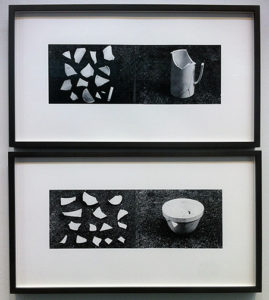

Replacing No. 1, 1975, Amikam Toren

Replacing No. 1, 1975, Amikam Toren

Apartment Windows, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1977.

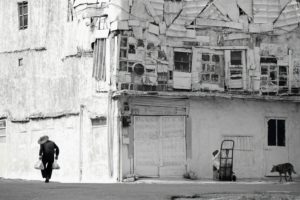

Apartment Windows, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1977. The Native Gaze 0005, by Chang-Ling, 2016

The Native Gaze 0005, by Chang-Ling, 2016 The Native Gaze 0006, by Chang-Ling, 2016

The Native Gaze 0006, by Chang-Ling, 2016 The Old Man and the House He Built, 2014, Wei-ming Yuan

The Old Man and the House He Built, 2014, Wei-ming Yuan

Andrey Boyreko (Left), Leonard Bernstein (Right)

Andrey Boyreko (Left), Leonard Bernstein (Right) Vadim Gluzman

Vadim Gluzman Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich

Giacomo Casanova (1725-1798)

Giacomo Casanova (1725-1798)

(Left) Franceso Guardi (Italian, 1712-1793) The Ridotto of Palazzo Dandolo at San Moise with Masked Figures Conversing ca. 1750. The ridotti were state sponsored gambling rooms, sometimes places of music and dancing. Everyone was required to wear masks which made it easier for thieves and prostitutes to mix with the elite. (Right) 18th c. Sedan chair which belonged to Alma Spreckles, founder of San Francisco’s Legion of Honor

(Left) Franceso Guardi (Italian, 1712-1793) The Ridotto of Palazzo Dandolo at San Moise with Masked Figures Conversing ca. 1750. The ridotti were state sponsored gambling rooms, sometimes places of music and dancing. Everyone was required to wear masks which made it easier for thieves and prostitutes to mix with the elite. (Right) 18th c. Sedan chair which belonged to Alma Spreckles, founder of San Francisco’s Legion of Honor

(Left)

(Left)

from left: Beethoven, Herbert Blomstedt, Garrick Ohlsson

from left: Beethoven, Herbert Blomstedt, Garrick Ohlsson

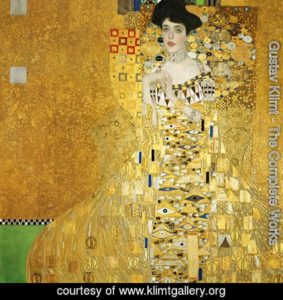

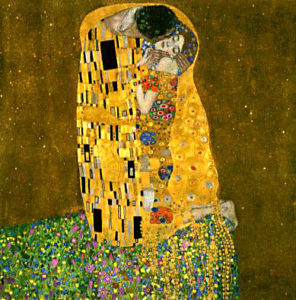

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (1907) (not part of this exhibition)

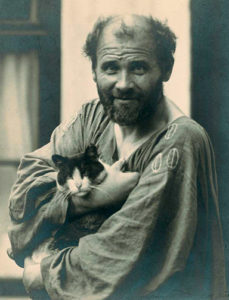

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (1907) (not part of this exhibition) Gustav Klimt and his Cat (Katze), photo by Moritz Nahr

Gustav Klimt and his Cat (Katze), photo by Moritz Nahr

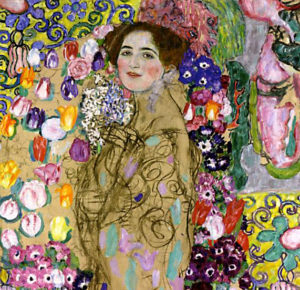

Klimt, The Virgin, 1913

Klimt, The Virgin, 1913 Emanuel Ax

Emanuel Ax

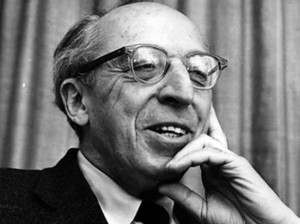

Arnold Schoenberg, photograph by Man Ray

Arnold Schoenberg, photograph by Man Ray Medieval woodcut of trickster, Tilll Eulenspiegel, courtesy, San Franciso Symphony

Medieval woodcut of trickster, Tilll Eulenspiegel, courtesy, San Franciso Symphony