On Sunday, January 25, Ivan Fischer led the extraordinary Budapest Festival Orchestra in an all Brahms program: Symphony No. 3 in F maj. Op. 90, and Symphony No.1 in C min., Op 68. Those individuals anywhere near San Francisco’s Civic Center will have seen a rounded, disk shape flying low and close to City Hall and the Opera House. It was the roof of Davies Symphony Hall which had lifted up and off the Hall at the conclusion of Symphony No. 1. What caused the lift off? Was it the energy created by the music itself or the force of the audience opening its four thousand eyes, leaning back and saying “oh!” surprised at its own exaltation? Sitting here, in Mountain View, just down the road from NASA Ames Research Center, one may leave the aeronautics to them, but it was not an unidentified flying object.

On Sunday, January 25, Ivan Fischer led the extraordinary Budapest Festival Orchestra in an all Brahms program: Symphony No. 3 in F maj. Op. 90, and Symphony No.1 in C min., Op 68. Those individuals anywhere near San Francisco’s Civic Center will have seen a rounded, disk shape flying low and close to City Hall and the Opera House. It was the roof of Davies Symphony Hall which had lifted up and off the Hall at the conclusion of Symphony No. 1. What caused the lift off? Was it the energy created by the music itself or the force of the audience opening its four thousand eyes, leaning back and saying “oh!” surprised at its own exaltation? Sitting here, in Mountain View, just down the road from NASA Ames Research Center, one may leave the aeronautics to them, but it was not an unidentified flying object. It was pure music rearranging the world. Symphony No. 3 opened the program. It is gorgeous, Brahms music which seems big enough to embrace the whole world. Mr. Fischer’s presentation took 7 fewer minutes than the older recording I listened to days later, wanting more of the experience. The BFO version was not rushed. It contained a sense of purpose and drive that made the whole symphony seem to pour forth without a pause. It opens with the Allegro con Brio making a declaration, presenting both a gentle dance and a struggle. There is an interplay amongst the strings in which their music seems to overlap like weaving. Despite the certain darkness behind the sprightly dance, a more positive theme re-emerges through the assault. There is no story or characterization in the music, and yet it is necessary to communicate its essence in the drama of language. This music carried in it the sweetness of our universe, even though the universe is impersonal forces. The Allegretto moves like the swaying of planets; it is so big and still intimate. It builds up to an enfolding theme that communicates human devotion. The winds suggest steps. Are they steps through the stars or human steps climbing lightfootedly through hills, rocking, turning through mists? The final, Allegro movement is busy, restless, quiet and suddenly louder. It surprises the listener and somehow suggests: we should have known. The call and response of the second movement reappears to remind us we were given hints and signs. In fact, we were shown. A spontaneous thought comes: “oh, no!” at the determined rebuilding of the music. It is wrestling with an angel. The horns make an announcement as they come over the hill, fighting and elevating at the same time. It is quiet music of our own atmosphere. Looking back, it brought to mind Robert Frost’s observation that “Earth’s the right place for love.” That is despite our limitations and because of them. There is Brahms’ Symphony No. 3 to encompass and present the love of Earth and the impossible human condition, the unbearable human condition which we might accept through Brahms’ triumph of beauty and understanding.

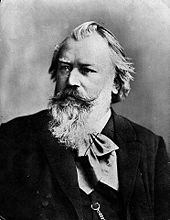

It was pure music rearranging the world. Symphony No. 3 opened the program. It is gorgeous, Brahms music which seems big enough to embrace the whole world. Mr. Fischer’s presentation took 7 fewer minutes than the older recording I listened to days later, wanting more of the experience. The BFO version was not rushed. It contained a sense of purpose and drive that made the whole symphony seem to pour forth without a pause. It opens with the Allegro con Brio making a declaration, presenting both a gentle dance and a struggle. There is an interplay amongst the strings in which their music seems to overlap like weaving. Despite the certain darkness behind the sprightly dance, a more positive theme re-emerges through the assault. There is no story or characterization in the music, and yet it is necessary to communicate its essence in the drama of language. This music carried in it the sweetness of our universe, even though the universe is impersonal forces. The Allegretto moves like the swaying of planets; it is so big and still intimate. It builds up to an enfolding theme that communicates human devotion. The winds suggest steps. Are they steps through the stars or human steps climbing lightfootedly through hills, rocking, turning through mists? The final, Allegro movement is busy, restless, quiet and suddenly louder. It surprises the listener and somehow suggests: we should have known. The call and response of the second movement reappears to remind us we were given hints and signs. In fact, we were shown. A spontaneous thought comes: “oh, no!” at the determined rebuilding of the music. It is wrestling with an angel. The horns make an announcement as they come over the hill, fighting and elevating at the same time. It is quiet music of our own atmosphere. Looking back, it brought to mind Robert Frost’s observation that “Earth’s the right place for love.” That is despite our limitations and because of them. There is Brahms’ Symphony No. 3 to encompass and present the love of Earth and the impossible human condition, the unbearable human condition which we might accept through Brahms’ triumph of beauty and understanding.  pictures: Ivan Fischer, Johannes Brahms, Ivan Fischer. The Symphony No. 1 has a misleading title. It is Brahms’ first symphony, but when he wrote it he was hardly a beginner. While music writers make much of how long Brahms waited to write his symphony and that he worked on it at least 15 years, he created chamber music, choruses, songs, piano music, and, for the orchestra, a piano concerto, two serenades, and the mighty German Requiem while some in the music world stood tapping their feet and looking at their calendars for that missing masterpiece, the symphony. Brahms pointed out, “you have no idea what it”s like to hear the footsteps of a giant like that behind you.” He meant Beethoven. He knew what was expected of him, but no one but Brahms knew how he would create his new symphony, a wholly Brahmsian symphony, when he was ready. It is fair for Symphony No. 1 to be called “the giant,” at about 45 minutes it is longer than the average symphony. It also is bigger in every sense. Two of the four movements use the notation, “sostenuto,” and sustained is definitely a word that matches the magnificent work. It has a complexity of themes and musical journeys in it, and all of them are so intricately worked together that each element seems to exist only as a part of the whole. This is a great work whose conception and invention upon close examination might make 21st century persons think it could only be worked out on a computer which could handle all the different threads of music. However, they would be wrong. Brahms carried so much of music and life in his being that the complexity he knit together also carries in its entirety the soul of human culture. It is not a Jeopardy contest. HIs symphony is a life and death matter. He found the answer is unity, and then he found the way to make it. It opens with repeated beats of the timpani. A musical anthem appears briefly, wrapping in and out of the whole design. The world grows quiet. There are challenges on all sides. A theme repeats like the delicate steps of feet on rocks crossing water. The timpani comes back and the plucked strings play out a mystery. Rhapsodic music comes and drifts off, marching is heard under the swelling music, a horn calls from afar. We are in a strange world or a familiar world which we have never looked at before. The Andante Sostenuto is smooth but never lulling. It seems to make demands but circles away to an embrace. Even in its quiet mood it is always bringing energy and spirit higher and stronger. It is like a sunrise but with a strong pulse behind it; there is always an awareness of darkness. The third movement does that thing that Brahms does. The listener suddenly finds her face drenched in tears never having thought, this will make me cry. It opens with a lovely, lively rhythmic tune like a child playing on the grass; the winds dance together.

pictures: Ivan Fischer, Johannes Brahms, Ivan Fischer. The Symphony No. 1 has a misleading title. It is Brahms’ first symphony, but when he wrote it he was hardly a beginner. While music writers make much of how long Brahms waited to write his symphony and that he worked on it at least 15 years, he created chamber music, choruses, songs, piano music, and, for the orchestra, a piano concerto, two serenades, and the mighty German Requiem while some in the music world stood tapping their feet and looking at their calendars for that missing masterpiece, the symphony. Brahms pointed out, “you have no idea what it”s like to hear the footsteps of a giant like that behind you.” He meant Beethoven. He knew what was expected of him, but no one but Brahms knew how he would create his new symphony, a wholly Brahmsian symphony, when he was ready. It is fair for Symphony No. 1 to be called “the giant,” at about 45 minutes it is longer than the average symphony. It also is bigger in every sense. Two of the four movements use the notation, “sostenuto,” and sustained is definitely a word that matches the magnificent work. It has a complexity of themes and musical journeys in it, and all of them are so intricately worked together that each element seems to exist only as a part of the whole. This is a great work whose conception and invention upon close examination might make 21st century persons think it could only be worked out on a computer which could handle all the different threads of music. However, they would be wrong. Brahms carried so much of music and life in his being that the complexity he knit together also carries in its entirety the soul of human culture. It is not a Jeopardy contest. HIs symphony is a life and death matter. He found the answer is unity, and then he found the way to make it. It opens with repeated beats of the timpani. A musical anthem appears briefly, wrapping in and out of the whole design. The world grows quiet. There are challenges on all sides. A theme repeats like the delicate steps of feet on rocks crossing water. The timpani comes back and the plucked strings play out a mystery. Rhapsodic music comes and drifts off, marching is heard under the swelling music, a horn calls from afar. We are in a strange world or a familiar world which we have never looked at before. The Andante Sostenuto is smooth but never lulling. It seems to make demands but circles away to an embrace. Even in its quiet mood it is always bringing energy and spirit higher and stronger. It is like a sunrise but with a strong pulse behind it; there is always an awareness of darkness. The third movement does that thing that Brahms does. The listener suddenly finds her face drenched in tears never having thought, this will make me cry. It opens with a lovely, lively rhythmic tune like a child playing on the grass; the winds dance together.

Then, a change to the amazing theme that grabs at the heart. It repeats with more emphasis, quiet steps in between, grows bigger, then quiet as the first theme comes back, reconsiders its place until all the music simply blows away. Brahms now shows us that music is made of silence as well as sound. Single notes pop into space. There is a long rest; again single notes pop into the environment as a sustained building of sound surges. After calm anticipation, the heart wringing theme returns, this time sounding positive and certain. It announces: I am here. This is all. It unwinds as there is a return of rushing, hurried, insistent music. Out of this a sound quietly asserts itself; a flute joins in until the whole orchestra marches forth to counter it. That theme returns, still certain. It is our anthem, and it persists even with the dark reminders from horns and strings. We come back. The dance elaborates itself struggling through the reworking of the theme. There are storms, threats; the theme slows, pauses, but never stops. It briefly becomes almost a lullaby. We are back to the dance on the hillside. One instrument is answered by the whole orchestra. The weather changes. A drum sounds as though the symphony is ending, but the music goes on, the clouds are clearing. There is the moment of take off; the music quickens; the horns announce: we are here. In a succession of counts; one, two, one two three it is over. The immense, mysterious experience is over. We knew that would happen; we did not know how; we did not really believe it would come. At this performance, the audience, stunned and inspired, wore out its hands applauding. The BFO musicians stood up and scrambled, moved from their places to other places, all holding sheet music. They sang a capella an Evening Serenade,Brahms’ Sommerabend, Op. 85, no.1, written for a poem by Heinrich Heine. It was beautiful.

Then, a change to the amazing theme that grabs at the heart. It repeats with more emphasis, quiet steps in between, grows bigger, then quiet as the first theme comes back, reconsiders its place until all the music simply blows away. Brahms now shows us that music is made of silence as well as sound. Single notes pop into space. There is a long rest; again single notes pop into the environment as a sustained building of sound surges. After calm anticipation, the heart wringing theme returns, this time sounding positive and certain. It announces: I am here. This is all. It unwinds as there is a return of rushing, hurried, insistent music. Out of this a sound quietly asserts itself; a flute joins in until the whole orchestra marches forth to counter it. That theme returns, still certain. It is our anthem, and it persists even with the dark reminders from horns and strings. We come back. The dance elaborates itself struggling through the reworking of the theme. There are storms, threats; the theme slows, pauses, but never stops. It briefly becomes almost a lullaby. We are back to the dance on the hillside. One instrument is answered by the whole orchestra. The weather changes. A drum sounds as though the symphony is ending, but the music goes on, the clouds are clearing. There is the moment of take off; the music quickens; the horns announce: we are here. In a succession of counts; one, two, one two three it is over. The immense, mysterious experience is over. We knew that would happen; we did not know how; we did not really believe it would come. At this performance, the audience, stunned and inspired, wore out its hands applauding. The BFO musicians stood up and scrambled, moved from their places to other places, all holding sheet music. They sang a capella an Evening Serenade,Brahms’ Sommerabend, Op. 85, no.1, written for a poem by Heinrich Heine. It was beautiful.

pictures: above, Yefim Bronfman; L-Rt, Brahms, Berg

pictures: above, Yefim Bronfman; L-Rt, Brahms, Berg