The San Francisco Symphony presented a marvelous program January 9-11; this audience member, there on Jan. 9th, found all three works fascinating and performed at the top. The Sf Symphony musicians found the heart of each selection. It was a wonderful concert. Conductor James Gaffigan was superb. In 2006-2009, he was the associate conductor for the SFS. He is now the General Music Director of Komische Oper Berlin and Music Director of the Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia, Valencia. In addition, he conducts in music centers around the world. Jeremy Constant, Concertmaster of the Marin Symphony was the Acting Concertmaster and led the First Violins with excellent musicianship.

The curtain raiser was a brief work by Missy Mazzoli’s Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres). Commissioned by the LA Philharmonic, its debut was 2014, in Los Angeles. This was its first performance at Davies Symphony Hall. Worried that the music would try its best to make me wish for Mozart, instead I wished it had not stopped so soon. It was a piece of imagination made musical. Performed with traditional instruments, there were also unusual sources of sounds: harmonicas, opera gong, and, pre-recorded, lion’s roar, and boombox. They blended and together lifted me up into what might be something like Out There

Missy Mazzoli, composer

Missy Mazzoli, composer

The astronauts now stuck in their space ship might wish to have a tape of it. Although they were supposed to come home to Earth, on June 5, 2024, the timing has not worked out. They now look forward to Earth in late March, 2025. Please Ms Mazzoli, write more musical theme “songs” for the astronauts.

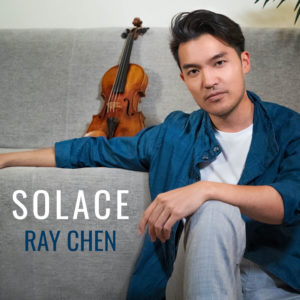

Violinist Ray Chen was the amazing soloist in Samuel Barber’s lyrical Violin Concerto, Opus14 (1940). This music is a heart full of emotion. Do not think of sentimental hearts; this concerto reminds the listeners of glory. Humans do get there sometimes, or they know can fly above. Ray Chen is a performer. He captures the stage, collaborates with each musician, and becomes at one with the Conductor. Ray Chen also has the charisma of a rock star. His technical abilities make the lyrical movements sound like truth, and his incredibly fast playing movements are just on the verge of super-human. Think Steph Curry: graceful, fast, absolutely on the point. It seems like magic, but it is human. After many bows, he gave us a suitably amazing encore. It was Eugene Ysaye’s Sonata, No. 2, “Obsession” (Prelude). The music began with an excerpt from Bach’s Partita No. 3 in E major for solo violin. Ysaye’ “obsession” with Bach led him to include quotes from the Bach Prelude. He also incorporates the “Dies Irae” of the Mass for the Dead. It was beautiful. Ysaye’s Sonata allows Mr. Chen to play something very special.

Samuel Barber, composer (1910-1981)

Samuel Barber, composer (1910-1981)

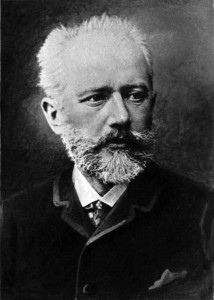

After the excitement of the Barber concerto, one hoped that the audience was ready for Prokofiev. When Maestro Gaffigan opened the program to tell us about what we would hear, he said that Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 in B-flat major, Opus 100 (1944) was one of– or maybe he said it was his favorite symphony. I am a great fan of Prokofiev. This symphony has it all. It is big, powerful, monumental but still musical in every way. He builds a world of music. Gaffigan took the opportunity for the SFS to play with everything: finesse, delicacy, bold gestures, and loud loud music. It was written during the war. On June 6, 1944, the Americans landed on Normandy beaches. Later in 1944, Russian forces broke into German territory. Prokofiev conducted the premiere of No. 5 at Moscow, 1945. He could hear artillery and explosions; he waited for the noises of war, and then started. Prokofiev felt hopeful and wrote about No. 5: “I conceived of it as glorifying the grandeur of the human spirit, praising the free and happy man—his strength, his generosity, and the purity of his soul.” Historically, the years that followed did not show humankind achieving its greatest character. Let’s hold on to Prokofiev’s moment feeling “the grandeur” of humanity and hope that Prokofiev could hold on to it, too.